Namibia

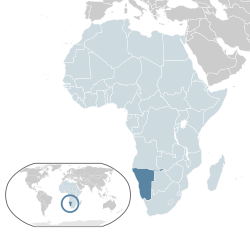

Namibia (/nəˈmɪbiə/ (![]() pulikizgani machemelo), /næˈ-/),[14][15] officially the Republic of Namibia, is a country in Southern Africa. Its western border is the Atlantic Ocean. It shares land borders with Zambia and Angola to the north, Botswana to the east and South Africa to the south and east. Although it does not border Zimbabwe, less than 200 metres (660 feet) of the Botswanan right bank of the Zambezi River separates the two countries. Namibia gained independence from South Africa on 21 March 1990, following the Namibian War of Independence. Its capital and largest city is Windhoek. Namibia is a member state of the United Nations (UN), the Southern African Development Community (SADC), the African Union (AU) and the Commonwealth of Nations.

pulikizgani machemelo), /næˈ-/),[14][15] officially the Republic of Namibia, is a country in Southern Africa. Its western border is the Atlantic Ocean. It shares land borders with Zambia and Angola to the north, Botswana to the east and South Africa to the south and east. Although it does not border Zimbabwe, less than 200 metres (660 feet) of the Botswanan right bank of the Zambezi River separates the two countries. Namibia gained independence from South Africa on 21 March 1990, following the Namibian War of Independence. Its capital and largest city is Windhoek. Namibia is a member state of the United Nations (UN), the Southern African Development Community (SADC), the African Union (AU) and the Commonwealth of Nations.

| Republic of Namibia Name in national languages

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Chiluso: "Unity, Liberty, Justice" | ||||||

| Nyimbo: "Namibia, Land of the Brave"

|

||||||

| [[File:|center|250px|alt=|]] | ||||||

| Msumba Waboma kweneso Msumba Usani | Windhoek | |||||

| Chiyowoyelo chaboma | English | |||||

| Viyowoyelo vyaboma | ||||||

| Viyowoyelo vyakumanyikwa vyamuvigaŵa | ||||||

| Mitundu ya Ŵanthu (2014) | ||||||

| Vipembezo |

|

|||||

| Mwenecharu | Namibian | |||||

| Mtundu wa Boma | Unitary dominant-party semi-presidential republic[9] | |||||

| - | President | Hage Geingob | ||||

| - | Vice President | Nangolo Mbumba | ||||

| - | Prime Minister | Saara Kuugongelwa | ||||

| - | Deputy Prime Minister | Netumbo Nandi-Ndaitwah | ||||

| - | Chief Justice | Peter Shivute | ||||

| - | Upper house | National Council | ||||

| - | Lower house | National Assembly | ||||

| Independence from South Africa | ||||||

| - | Constitution | 9 February 1990 | ||||

| - | Independence | 21 March 1990 | ||||

| Ukulu wa Malo | ||||||

| - | Malo | 825,615 km2 (34th) 318,696 sq mi |

||||

| - | Maji (%) | negligible | ||||

| Chiŵelengelo cha ŵanthu | ||||||

| - | 2023 estimate | 2,777,232[10] (141th) | ||||

| - | Density | 3.2/km2 (235th) 6.6/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2023 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | |||||

| - | Per capita | |||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2023 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | |||||

| - | Per capita | |||||

| Gini (2015) | 59.1[12] high |

|||||

| HDI (2021) | medium ·139th |

|||||

| Ndalama | Namibian dollar (NAD) South African rand (ZAR) |

|||||

| Mtundu Wanyengo | CAST (UTC+2) | |||||

| Kalembelo kasiku | dd/mm/yyyy | |||||

| Woko la galimoto | left | |||||

| Intaneti yacharu | .na | |||||

The driest country in sub-Saharan Africa,[16] Namibia has been inhabited since pre-historic times by the San, Damara and Nama people. Around the 14th century, immigrating Bantu peoples arrived as part of the Bantu expansion. Since then, the Bantu groups, the largest being the Ovambo, have dominated the population of the country; since the late 19th century, they have constituted a majority. Today Namibia is one of the least densely populated countries in the world.

It has a population of 2.55 million people and is a stable multi-party parliamentary democracy. Agriculture, tourism and the mining industry – including mining for gem diamonds, uranium, gold, silver and base metals – form the basis of its economy, while the manufacturing sector is comparatively small.

In 1884, the German Empire established rule over most of the territory, forming a colony known as German South West Africa. Between 1904 and 1908, it perpetrated a genocide against the Herero and Nama people. German rule ended in 1915 with a defeat by South African forces. In 1920, after the end of World War I, the League of Nations mandated administration of the colony to South Africa. As mandatory power, South Africa imposed its laws, including racial classifications and rules. From 1948, with the National Party elected to power, this included South Africa applying apartheid to what was then known as South West Africa. In the later 20th century, uprisings and demands for political representation by native African political activists seeking independence resulted in the UN assuming direct responsibility over the territory in 1966, but the country of South Africa maintained de facto rule. In 1973, the UN recognised the South West Africa People's Organisation (SWAPO) as the official representative of the Namibian people. Following continued guerrilla warfare, Namibia obtained independence in 1990. However, Walvis Bay and the Penguin Islands remained under South African control until 1994.

History

lembaEtymology

lembaThe name of the country is derived from the Namib desert, the oldest desert in the world.[17] The name Namib itself is of Nama origin and means "vast place". That word for the country was chosen by Mburumba Kerina, who originally proposed the name the "Republic of Namib".[18] Before its independence in 1990, the area was known first as German South-West Africa (Deutsch-Südwestafrika), then as South West Africa, reflecting the colonial occupation by the Germans and South Africans.

Pre-colonial period

lembaThe dry lands of Namibia have been inhabited since prehistoric times by the San, Damara, and Nama. For thousands of years, the Khoisan peoples of Southern Africa maintained a nomadic life, the Khoikhoi as pastoralists and the San people as hunter-gatherers. Around the 14th century, immigrating Bantu people began to arrive during the Bantu expansion from central Africa.[19]

From the late 18th century onward, Oorlam people from Cape Colony crossed the Orange River and moved into the area that today is southern Namibia.[20] Their encounters with the nomadic Nama tribes were largely peaceful. They received the missionaries accompanying the Oorlam very well,[21] granting them the right to use waterholes and grazing against an annual payment.[22] On their way further north, however, the Oorlam encountered clans of the OvaHerero at Windhoek, Gobabis, and Okahandja, who resisted their encroachment. The Nama-Herero War broke out in 1880, with hostilities ebbing only after the German Empire deployed troops to the contested places and cemented the status quo among the Nama, Oorlam, and Herero.[23]

In 1878, the Cape of Good Hope, then a British colony, annexed the port of Walvis Bay and the offshore Penguin Islands; these became an integral part of the new Union of South Africa at its creation in 1910.

The first Europeans to disembark and explore the region were the Portuguese navigators Diogo Cão in 1485[24] and Bartolomeu Dias in 1486, but the Portuguese did not try to claim the area. Like most of the interior of Sub-Saharan Africa, Namibia was not extensively explored by Europeans until the 19th century. At that time traders and settlers came principally from Germany and Sweden. In 1870, Finnish missionaries came to the northern part of Namibia to spread the Lutheran religion among the Ovambo and Kavango people.[25] In the late 19th century, Dorsland Trekkers crossed the area on their way from the Transvaal to Angola. Some of them settled in Namibia instead of continuing their journey.

German rule

lembaNamibia became a German colony in 1884 under Otto von Bismarck to forestall perceived British encroachment and was known as German South West Africa (Deutsch-Südwestafrika).[26] The Palgrave Commission by the British governor in Cape Town determined that only the natural deep-water harbour of Walvis Bay was worth occupying and thus annexed it to the Cape province of British South Africa.

In 1897, a rinderpest epidemic caused massive cattle die-offs of an estimated 95% of cattle in southern & central Namibia. In response the German colonizers set up a veterinary cordon fence known as the Red Line.[27] In 1907 this fence then broadly defined the boundaries for the first Police Zone.[28]

From 1904 to 1907, the Herero and the Namaqua took up arms against brutal German colonialism. In a calculated punitive action by the German occupiers, government officials ordered the extinction of the natives in the OvaHerero and Namaqua genocide. In what has been called the "first genocide of the 20th century",[29] the Germans systematically killed 10,000 Nama (half the population) and approximately 65,000 Herero (about 80% of the population).[30][31] The survivors, when finally released from detention, were subjected to a policy of dispossession, deportation, forced labour, racial segregation, and discrimination in a system that in many ways foreshadowed the apartheid established by South Africa in 1948.

Most Africans were confined to so-called native territories, which under South African rule after 1949 were turned into "homelands" (Bantustans). Some historians have speculated that the German genocide in Namibia was a model for the Nazis in the Holocaust.[32] The memory of genocide remains relevant to ethnic identity in independent Namibia and to relations with Germany.[33] The German minister for aid development apologised for the Namibian genocide in 2004, however, the German government distanced itself from this apology.[34][35]

South African mandate

lembaDuring World War I, South African troops under General Louis Botha occupied the territory and deposed the German colonial administration. The end of the war and the Treaty of Versailles resulted in South West Africa remaining a possession of South Africa, at first as a League of Nations mandate, until 1990.[36] The mandate system was formed as a compromise between those who advocated for an Allied annexation of former German and Ottoman territories and a proposition put forward by those who wished to grant them to an international trusteeship until they could govern themselves.[36] It permitted the South African government to administer South West Africa until that territory's inhabitants were prepared for political self-determination.[37] South Africa interpreted the mandate as a veiled annexation and made no attempt to prepare South West Africa for future autonomy.[37]

As a result of the Conference on International Organization in 1945, the League of Nations was formally superseded by the United Nations (UN) and former League mandates by a trusteeship system. Article 77 of the United Nations Charter stated that UN trusteeship "shall apply...to territories now held under mandate"; furthermore, it would "be a matter of subsequent agreement as to which territories in the foregoing territories will be brought under the trusteeship system and under what terms".[38] The UN requested all former League of Nations mandates be surrendered to its Trusteeship Council in anticipation of their independence.[38] South Africa declined to do so and instead requested permission from the UN to formally annex South West Africa, for which it received considerable criticism.[38] When the UN General Assembly rejected this proposal, South Africa dismissed its opinion and began solidifying control of the territory.[38] The UN Generally Assembly and Security Council responded by referring the issue to the International Court of Justice (ICJ), which held a number of discussions on the legality of South African rule between 1949 and 1966.[39]

South Africa began imposing apartheid, its codified system of racial segregation and discrimination, on South West Africa during the late 1940s.[40] Black South West Africans were subject to pass laws, curfews, and a host of residential regulations that restricted their movement.[40] Development was concentrated in the southern region of the territory adjacent to South Africa, known as the "Police Zone", where most of the major settlements and commercial economic activity were located.[41] Outside the Police Zone, indigenous peoples were restricted to theoretically self-governing tribal homelands.[41]

During the late 1950s and early 1960s, the accelerated decolonisation of Africa and mounting pressure on the remaining colonial powers to grant their colonies self-determination resulted in the formation of nascent nationalist parties in South West Africa.[42] Movements such as the South West African National Union (SWANU) and the South West African People's Organisation advocated for the formal termination of South Africa's mandate and independence for the territory.[42] In 1966, following the ICJ's controversial ruling that it had no legal standing to consider the question of South African rule, SWAPO launched an armed insurgency that escalated into part of a wider regional conflict known as the South African Border War.[43]

In 1971 Namibian contract workers led a general strike against the contract system and in support of independence.[44] Some of the striking workers would later join SWAPO's PLAN[45] as part of the South African Border War.

Independence

lembaAs SWAPO's insurgency intensified, South Africa's case for annexation in the international community continued to decline.[46] The UN declared that South Africa had failed in its obligations to ensure the moral and material well-being of South West Africa's indigenous inhabitants, and had thus disavowed its own mandate.[47] On 12 June 1968, the UN General Assembly adopted a resolution proclaiming that, in accordance with the desires of its people, South West Africa be renamed Namibia.[47] United Nations Security Council Resolution 269, adopted in August 1969, declared South Africa's continued occupation of Namibia illegal.[47][48] In recognition of this landmark decision, SWAPO's armed wing was renamed the People's Liberation Army of Namibia (PLAN).[49]

Namibia became one of several flashpoints for Cold War proxy conflicts in southern Africa during the latter years of the PLAN insurgency.[50] The insurgents sought out weapons and sent recruits to the Soviet Union for military training.[51] As the PLAN war effort gained momentum, the Soviet Union and other sympathetic states such as Cuba continued to increase their support, deploying advisers to train the insurgents directly as well as supplying more weapons and ammunition.[52] SWAPO's leadership, dependent on Soviet, Angolan, and Cuban military aid, positioned the movement firmly within the socialist bloc by 1975.[53] This practical alliance reinforced the external perception of SWAPO as a Soviet proxy, which dominated Cold War rhetoric in South Africa and the United States.[41] For its part, the Soviet Union supported SWAPO partly because it viewed South Africa as a regional Western ally.[54]

Growing war weariness and the reduction of tensions between the superpowers compelled South Africa, Angola, and Cuba to accede to the Tripartite Accord, under pressure from both the Soviet Union and the United States.[55] South Africa accepted Namibian independence in exchange for Cuban military withdrawal from the region and an Angolan commitment to cease all aid to PLAN.[56] PLAN and South Africa adopted an informal ceasefire in August 1988, and a United Nations Transition Assistance Group (UNTAG) was formed to monitor the Namibian peace process and supervise the return of refugees.[57] The ceasefire was broken after PLAN made a final incursion into the territory, possibly as a result of misunderstanding UNTAG's directives, in March 1989.[58] A new ceasefire was later imposed with the condition that the insurgents were to be confined to their external bases in Angola until they could be disarmed and demobilised by UNTAG.[57][59]

By the end of the 11-month transition period, the last South African troops had been withdrawn from Namibia, all political prisoners granted amnesty, racially discriminatory legislation repealed, and 42,000 Namibian refugees returned to their homes.[53] Just over 97% of eligible voters participated in the country's first parliamentary elections held under a universal franchise.[60] The United Nations plan included oversight by foreign election observers in an effort to ensure a free and fair election. SWAPO won a plurality of seats in the Constituent Assembly with 57% of the popular vote.[60] This gave the party 41 seats, but not a two-thirds majority, which would have enabled it to draft the constitution on its own.[60]

The Namibian Constitution was adopted in February 1990. It incorporated protection for human rights and compensation for state expropriations of private property and established an independent judiciary, legislature, and an executive presidency (the constituent assembly became the national assembly). The country officially became independent on 21 March 1990.[61][25] Sam Nujoma was sworn in as the first President of Namibia at a ceremony attended by Nelson Mandela of South Africa (who had been released from prison the previous month) and representatives from 147 countries, including 20 heads of state.[62] In 1994, shortly before the first multiracial elections in South Africa, that country ceded Walvis Bay to Namibia.[63]

After independence

lembaSince independence Namibia has completed the transition from white minority apartheid rule to parliamentary democracy. Multiparty democracy was introduced and has been maintained, with local, regional and national elections held regularly. Several registered political parties are active and represented in the National Assembly, although the SWAPO has won every election since independence.[64] The transition from the 15-year rule of President Nujoma to his successor Hifikepunye Pohamba in 2005 went smoothly.[65]

Since independence, the Namibian government has promoted a policy of national reconciliation. It issued an amnesty for those who fought on either side during the liberation war. The civil war in Angola spilled over and adversely affected Namibians living in the north of the country. In 1998, Namibia Defence Force (NDF) troops were sent to the Democratic Republic of the Congo as part of a Southern African Development Community (SADC) contingent.

In 1999, the national government quashed a secessionist attempt in the northeastern Caprivi Strip.[65] The Caprivi conflict was initiated by the Caprivi Liberation Army (CLA), a rebel group led by Mishake Muyongo. It wanted the Caprivi Strip to secede and form its own society.

In December 2014, Prime Minister Hage Geingob, the candidate of ruling SWAPO, won the presidential elections, taking 87% of the vote. His predecessor, President Hifikepunye Pohamba, also of SWAPO, had served the maximum two terms allowed by the constitution.[66] In December 2019, President Hage Geingob was re-elected for a second term, taking 56.3% of the vote.[67]

Geography

lembaAt 825,615 km2 (318,772 sq mi),[68] Namibia is the world's thirty-fourth largest country (after Venezuela). It lies mostly between latitudes 17° and 29°S (a small area is north of 17°), and longitudes 11° and 26°E.

Being situated between the Namib and the Kalahari deserts, Namibia has the least rainfall of any country in sub-Saharan Africa.[69]

The Namibian landscape consists generally of five geographical areas, each with characteristic abiotic conditions and vegetation, with some variation within and overlap between them: the Central Plateau, the Namib, the Great Escarpment, the Bushveld, and the Kalahari Desert.

The Central Plateau runs from north to south, bordered by the Skeleton Coast to the northwest, the Namib Desert and its coastal plains to the southwest, the Orange River to the south, and the Kalahari Desert to the east. The Central Plateau is home to the highest point in Namibia at Königstein elevation 2,606 metres (8,550 ft).[70]

The Namib is a broad expanse of hyper-arid gravel plains and dunes that stretches along Namibia's entire coastline. It varies between 100 and 200 kilometres (60 and 120 mi) in width. Areas within the Namib include the Skeleton Coast and the Kaokoveld in the north and the extensive Namib Sand Sea along the central coast.[17]

The Great Escarpment swiftly rises to over 2,000 metres (7,000 ft). Average temperatures and temperature ranges increase further inland from the cold Atlantic waters, while the lingering coastal fogs slowly diminish. Although the area is rocky with poorly developed soils, it is significantly more productive than the Namib Desert. As summer winds are forced over the Escarpment, moisture is extracted as precipitation.[71]

The Bushveld is found in north-eastern Namibia along the Angolan border and in the Caprivi Strip. The area receives a significantly greater amount of precipitation than the rest of the country, averaging around 400 mm (16 in) per year. The area is generally flat and the soils sandy, limiting their ability to retain water and support agriculture.[72]

The Kalahari Desert, an arid region that extends into South Africa and Botswana, is one of Namibia's well-known geographical features. The Kalahari, while popularly known as a desert, has a variety of localised environments, including some verdant and technically non-desert areas. The Succulent Karoo is home to over 5,000 species of plants, nearly half of them endemic; approximately 10 percent of the world's succulents are found in the Karoo.[73][74] The reason behind this high productivity and endemism may be the relatively stable nature of precipitation.[75]

Namibia's Coastal Desert is one of the oldest deserts in the world. Its sand dunes, created by the strong onshore winds, are the highest in the world.[76] Because of the location of the shoreline, at the point where the Atlantic's cold water reaches Africa's hot climate, often extremely dense fog forms along the coast.[77] Near the coast there are areas where the dune-hummocks are vegetated.[78] Namibia has rich coastal and marine resources that remain largely unexplored.[79]

The Caprivi Strip extends east from the northeastern corner of the country.

Climate

lembaNamibia extends from 17°S to 25°S latitude: climatically the range of the sub-Tropical High Pressure Belt. Its overall climate description is arid, descending from the Sub-Humid [mean rain above 500 mm (20 in)] through Semi-Arid [between 300 and 500 mm (12 and 20 in)] (embracing most of the waterless Kalahari) and Arid [from 150 to 300 mm (6 to 12 in)] (these three regions are inland from the western escarpment) to the Hyper-Arid coastal plain [less than 100 mm (4 in)]. Temperature maxima are limited by the overall elevation of the entire region: only in the far south, Warmbad for instance, are maxima above 40 °C (104 °F) recorded.[80]

Typically the sub-Tropical High Pressure Belt, with frequent clear skies, provides more than 300 days of sunshine per year. It is situated at the southern edge of the tropics; the Tropic of Capricorn cuts the country about in half. The winter (June – August) is generally dry. Both rainy seasons occur in summer: the small rainy season between September and November, the big one between February and April.[81] Humidity is low, and average rainfall varies from almost zero in the coastal desert to more than 600 mm (24 in) in the Caprivi Strip. Rainfall is highly variable, and droughts are common.[82] In the summer of 2006/07 the rainfall was recorded far below the annual average.[83] In May 2019, Namibia declared a state of emergency in response to the drought,[84] and extended it by additional 6 months in October 2019.[85]

Weather and climate in the coastal area are dominated by the cold, north-flowing Benguela Current of the Atlantic Ocean, which accounts for very low precipitation (50 mm (2 in) per year or less), frequent dense fog, and overall lower temperatures than in the rest of the country.[82] In Winter, occasionally a condition known as Bergwind (German for "mountain wind") or Oosweer (Afrikaans for "east weather") occurs, a hot dry wind blowing from the inland to the coast. As the area behind the coast is a desert, these winds can develop into sand storms, leaving sand deposits in the Atlantic Ocean that are visible on satellite images.[86]

The Central Plateau and Kalahari areas have wide diurnal temperature ranges of up to 30C (54F).[82]

Efundja, the annual seasonal flooding of the northern parts of the country, often causes not only damage to infrastructure but loss of life.[87] The rains that cause these floods originate in Angola, flow into Namibia's Cuvelai-Etosha Basin, and fill the oshanas (Oshiwambo: flood plains) there. The worst floods so far[update] occurred in March 2011 and displaced 21,000 people.[88]

Water sources

lembaNamibia is the driest country in sub-Saharan Africa and depends largely on groundwater. With an average rainfall of about 350 mm (14 in) per annum, the highest rainfall occurs in the Caprivi Strip in the northeast (about 600 mm (24 in) per annum) and decreases in a westerly and southwesterly direction to as little as 50 mm (2 in) and less per annum at the coast. The only perennial rivers are found on the national borders with South Africa, Angola, Zambia, and the short border with Botswana in the Caprivi Strip. In the interior of the country, surface water is available only in the summer months when rivers are in flood after exceptional rainfalls. Otherwise, surface water is restricted to a few large storage dams retaining and damming up these seasonal floods and their run-off. Where people do not live near perennial rivers or make use of the storage dams, they are dependent on groundwater. Even isolated communities and those economic activities located far from good surface water sources, such as mining, agriculture, and tourism, can be supplied from groundwater over nearly 80% of the country.[89]

More than 100,000 boreholes have been drilled in Namibia over the past century. One third of these boreholes have been drilled dry.[90] An aquifer called Ohangwena II, on both sides of the Angola-Namibia border, was discovered in 2012. It has been estimated to be capable of supplying a population of 800,000 people in the North for 400 years, at the current (2018) rate of consumption.[91] Experts estimate that Namibia has 7,720 km3 (1,850 cu mi) of underground water.[92][93]

According to African Folder, a sewage-to-water treatment project in Namibia not only provides citizens with safe drinking water but also boosts productivity by 6% per year. All pollutants and impurities are removed using cutting-edge "multi-barrier" technology, which includes residual chlorination, ozone treatment, and ultra membrane filtration. Strict bio-monitoring methods are also used throughout the process to ensure high-quality, safe drinking water.[94]

Communal Wildlife Conservancies

lembaMu vyaru vichoko waka pa caru cose capasi, dango la boma la Namibia likuyowoyapo comene za kuvikilira na kuvikilira vinthu vyakuthupi. Ndime ya 95 yikuti, "Boma likulimbikira kukhozga na kusungilira umoyo uwemi wa ŵanthu pakutolera ndondomeko ya vyaru ivyo vikulondezga fundo izi: kusungilira vyamoyo, vinthu ivyo vikukhumbikwa pa umoyo wa ŵanthu, na vinthu ivyo vikukhumbikwa pa umoyo wa ŵanthu ku Namibia, kweniso kugwiliskira ntchito vinthu ivyo vikukhumbikwa pa umoyo wa ŵanthu ku Namibia kuti ŵanthu wose ŵa mu charu ichi ŵasange chandulo sono na munthazi".

Mu 1993, boma liphya la Namibia likapokera ndalama kufuma ku wupu wa United States Agency for International Development (USAID) kwizira mu pulogiramu yawo ya Living in a Finite Environment (LIFE). Unduna wa vya Munda na Ulendo, na wovwiri wa ndalama kufuma ku mawupu nga ni USAID, Endangered Wildlife Trust, WWF, na Canadian Ambassador's Fund, wose pamoza ŵakuzenga ndondomeko ya kovwira ŵanthu pa nkhani ya kulongozga vinthu vyakuthupi (CBNRM). Cholinga chachikulu cha polojekitiyi ndikuthandizira kusamalira zachilengedwe mwa kupereka ufulu kwa anthu ammudzi kuti azisamalira zachilengedwe ndi zokopa alendo.[95]

Government and politics

lembaNamibia ni chalo icho chili na nduna yimoza. Pulezidenti wa ku Namibia wakusankhika kwa vyaka vinkhondi ndipo ni mulongozgi wa boma. Wose awo ŵali mu wupu wa boma ŵakuŵa na udindo ku wupu wa malango.[97][98]

The Constitution of Namibia outlines the following as the organs of the country's government:[99]

- Executive: executive power is exercised by the President and the Government.

- Legislature: Namibia has a bicameral Parliament with the National Assembly as lower house, and the National Council as the upper house.[100]

- Judiciary: Namibia has a system of courts that interpret and apply the law in the name of the state.

While the constitution envisaged a multi-party system for Namibia's government, the SWAPO party has been dominant since independence in 1990.[101]

Foreign relations

lembaBoma la Namibia likulondezga ndondomeko ya vyaru vyakupambanapambana, ndipo likulutilira kukolerana na vyaru ivyo vikawovwira pa nkhondo ya wanangwa, kusazgapo Cuba. Boma la Namibia lili na ŵasilikari ŵacoko waka kweniso ndarama zakusuzga, ntheura likukhumba kukhozga ubali wake na vyaru vya kumwera kwa Africa. Nga ni membala wa wupu wa Southern African Development Community, caru ca Namibia cikukhumba kuti ciŵe cakukolerana na vyaru vinyake. Pa 23 Epulero 1990, caru ici cikaŵa ciŵaro ca nambara 160 ca UN. Pa zuŵa ilo likapokelera wanangwa wake, likaŵa chalo cha nambara 50 mu Commonwealth of Nations.

Military

lembaKukwambilira kwa chaka cha 2020, The Global Firepower Index (GFP) yikayowoya kuti ŵasilikari ŵa ku Namibia ŵali pa malo gha 126 pa vyaru 137. Pa vyaru 34 vya mu Africa, Namibia nayo yili pa malo gha 28. Nangauli vikaŵa nthena, ndalama izo boma likagwiliskiranga nchito pa mulimo wa kuvikilira caru zikaŵa N$5,885 miliyoni (kuyana na ndalama izo zikaŵapo mu cilimika cakwambilira, zikakhira na 1.2%). Pafupifupi madola 6 biliyoni gha ku Namibia (US$411 miliyoni mu 2021) Unduna wa Chivikiliro ukupokela ndalama zinayi kufuma ku boma pa unduna uliwose.

Ku Namibia kulije ŵalwani mu cigaŵa ici, nangauli kuli kukwesana pa nkhani ya mphaka na mapulani gha kuzenga.

Ndondomeko ya boma la Namibia yikulongosora kuti mulimo wa ŵasilikari ni "kuvikilira caru na vinthu vya caru". Namibia yikapanga gulu la ŵasilikari (NDF), ilo likapangika na ŵasilikari awo ŵakasuzgikanga na nkhondo iyo yikacitika kwa vilimika 23: gulu la ŵasilikari la People's Liberation Army of Namibia (PLAN) na South West African Territorial Force (SWATF). Ŵabritishi ŵakanozga pulani ya umo ŵasilikari aŵa ŵakeneranga kukolerana, ndipo ŵakamba kusambizga ŵasilikari ŵa NDF, awo ŵakaŵa na likuru la ŵasilikari na magulu ghankhondi.

Ŵasilikari ŵa ku Kenya awo ŵakagwiranga nchito na gulu la United Nations Transitional Assistance Group (UNTAG) ŵakakhala ku Namibia kwa myezi yitatu kuti ŵasambizge ŵasilikari ŵa NDF kweniso kuti ŵakhazikiske mtende ku mpoto kwa charu ichi. Kuyana na ivyo Unduna wa Vyankhondo wa ku Namibia ukayowoya, ŵanalume na ŵanakazi ŵakukwana 7,500 ndiwo ŵanjirenge usilikari.

Mkulu wa Nkhondo ya Namibia ndi Air Vice Marshal Martin Kambulu Pinehas (kuyambira pa 1 April 2020).

Mu 2017, charu cha Namibia chikasayinira phangano la UN lakukanizga kugwiliskira nchito vilwero vya nyukiliya.[102]

Administrative divisions

lembaCharu cha Namibia chili kugaŵikana mu vigaŵa 14, ivyo navyo vili kugaŵikana mu vigaŵa 121. Kugaŵikana kwa Namibia kukupangika na ma komiti agho ghakupanga mphaka ndipo ghakupokelereka panji kukanizgika na wupu wa National Assembly. Kufuma apo boma ili likambira, makomiti ghanayi ghakupanga mphaka ya vigaŵa ghakapeleka mulimo wawo, ndipo laumaliro likaŵa mu 2013 ndipo likalongozgekanga na Mweruzgi Alfred Siboleka.

Ŵalaraŵalara ŵa vigaŵa ŵakusoleka mwakudunjika na ŵanthu awo ŵakukhala mu vigaŵa vyawo.

Boma la ku Namibia lingaŵa na maboma gha vigaŵa viŵiri (mabungwe gha chigaŵa chakwamba na chigaŵa chachiŵiri), maboma gha tawuni panji gha muzi.[103]

Human rights

lembaNamibia njimoza mwa vyaru vya mu Africa ivyo vili na wanangwa ndiposo vya demokarasi, ndipo boma lake likuvikilira wanangwa wa ŵanthu. Ndipouli, nkhani zikuru zikusazgapo vimbundi vya mu boma na unandi wa ŵakayidi. Kweniso ŵanthu awo ŵachimbira kwawo ŵakuzomerezgeka yayi kwenda mwakufwatuka.

Dango ili likwendera yayi, kweni kugonana kwa ŵanalume panji ŵanakazi ŵekhaŵekha nkhukanizgika mu Namibia. Ŵanthu ŵanandi ŵakutemwera yayi panji kutinkhana na ŵanthu awo ŵakugonana na ŵanalume panji ŵanakazi ŵanyawo. Ŵalaraŵalara ŵanyake ŵa boma la Namibia na ŵanthu ŵakumanyikwa, nga ni Mulongozgi wa Boma la Namibia, John Walters, na mwanakazi wakwamba, Monica Geingos, ŵakukhumba kuti kugonana kwa ŵanalume panji ŵanakazi ŵekhaŵekha kulekerethu ndipo ŵakukhumba kuti ŵanalume panji ŵanakazi ŵekhaŵekha ŵaŵe na wanangwa wakuyana na wanangwa wawo.[104][105]

Mu Novembala 2018, vikalembeka kuti 32% ya ŵanakazi ŵa vyaka vyapakati pa 15 na 49 ŵakasuzgika na nkhaza na nkhaza za mu nyumba izo ŵakachitikanga na ŵawoli panji ŵabwezi ŵawo, ndipo 29.5% ya ŵanalume ŵakagomezganga kuti nkhaza izo ŵakachitiranga ŵawoli panji ŵabwezi ŵawo zikaŵa zakwenelera. Ndondomeko ya boma la Namibia yikupanga wanangwa, wanangwa na wanangwa wakuyana kwa ŵanakazi mu Namibia ndipo gulu la SWAPO, ilo liri pa mazaza mu Namibia, lakhazikiska ndondomeko yakuti ŵanakazi wose ŵaŵe na wanangwa wakuyana mu boma.[106][107]

Economy

lembaNamibia's economy is tied closely to South Africa's due to their shared history.[108][109] The largest economic sectors are mining (10.4% of the gross domestic product in 2009), agriculture (5.0%), manufacturing (13.5%), and tourism (14.5%).[110]

Namibia has a highly developed banking sector with modern infrastructures, such as online banking and cellphone banking. The Bank of Namibia (BoN) is the central bank of Namibia responsible for performing all other functions ordinarily performed by a central bank. There are five BoN authorised commercial banks in Namibia: Bank Windhoek, First National Bank, Nedbank, Standard Bank and Small and Medium Enterprises Bank.[111] Namibia's economy is characterised by a divide between the formal and the informal economies, which is in part aggravated by the legacy of apartheid spatial planning.[112]

According to the Namibia Labour Force Survey Report 2012, conducted by the Namibia Statistics Agency, the country's unemployment rate is 27.4%.[113] "Strict unemployment" (people actively seeking a full-time job) stood at 20.2% in 2000, 21.9% in 2004 and spiralled to 29.4% in 2008. Under a broader definition (including people who have given up searching for employment) unemployment rose to 36.7% in 2004. This estimate considers people in the informal economy as employed. Labour and Social Welfare Minister Immanuel Ngatjizeko praised the 2008 study as "by far superior in scope and quality to any that has been available previously",[114] but its methodology has also received criticism.[115]

In 2004 a labour act was passed to protect people from job discrimination stemming from pregnancy and HIV/AIDS status. In early 2010 the Government tender board announced that "henceforth 100 per cent of all unskilled and semi-skilled labour must be sourced, without exception, from within Namibia".[116]

In 2013, global business and financial news provider, Bloomberg, named Namibia the top emerging market economy in Africa and the 13th best in the world. Only four African countries made the Top 20 Emerging Markets list in the March 2013 issue of Bloomberg Markets magazine, and Namibia was rated ahead of Morocco (19th), South Africa (15th), and Zambia (14th). Worldwide, Namibia also fared better than Hungary, Brazil, and Mexico. Bloomberg Markets magazine ranked the top 20 based on more than a dozen criteria. The data came from Bloomberg's own financial-market statistics, IMF forecasts and the World Bank. The countries were also rated on areas of particular interest to foreign investors: the ease of doing business, the perceived level of corruption and economic freedom. To attract foreign investment, the government has made improvement in reducing red tape resulted from excessive government regulations, making Namibia one of the least bureaucratic places to do business in the region. Facilitation payments are occasionally demanded by customs due to cumbersome and costly customs procedures.[117] Namibia is also classified as an Upper Middle Income country by the World Bank, and ranks 87th out of 185 economies in terms of ease of doing business.[118]

The cost of living in Namibia is relatively high because most goods, including cereals, need to be imported. Its capital city, Windhoek, is the 150th most expensive place in the world for expatriates to live.[119]

Taxation in Namibia includes personal income tax, which is applicable to the total taxable income of an individual. All individuals are taxed at progressive marginal rates over a series of income brackets. The value-added tax (VAT) is applicable to most of the commodities and services.[120]

Despite the remote nature of much of the country, Namibia has seaports, airports, highways, and railways (narrow-gauge). It seeks to become a regional transportation hub; it has an important seaport and several landlocked neighbours. The Central Plateau already serves as a transportation corridor from the more densely populated north to South Africa, the source of four-fifths of Namibia's imports.[121]

Agriculture

lembaPafupifupi hafu ya ŵanthu ŵa mu Namibia ŵakuthemba ulimi kuti ŵasange vyakukhumbikwa pa umoyo, kweni nanga ni sono ŵakukhumbikwira kunjizga vyakurya vinyake mu charu. Nangauli ciŵelengero ca ŵanthu awo ŵakukhala mu caru ici cikujumpha ciŵelengero ca ŵanthu awo ŵakukhala mu vyaru vikavu comene vya mu Africa, kweni ŵanthu ŵanandi mu caru ici ŵakukhala mu mizi ndipo ŵakukhumbikwira ndalama zinandi kuti ŵasange vyakukhumbikwa pa umoyo. Ku Namibia ndiko kuli ŵanthu ŵanandi chomene ŵambura kupokera ndalama zakukwana, cifukwa cakuti ŵanthu ŵanandi ŵakukhala mu matawuni, ndipo ŵanandi ŵakukhala mu mizi. Ntheura, pa mdauko uwu, pali ŵanthu awo ŵakuthemba yayi chuma kuti ŵasange vyakukhumbikwa pa umoyo. Nangauli charu cha Namibia chili na vyakurya vyakukwana 1 peresenti yayi, kweni ŵanthu pafupifupi hafu ya ŵanthu wose ŵali mu ulimi..[121]

Pafupifupi hafu ya minda ya ku Namibia yili mu mawoko gha ŵalimi pafupifupi 4,000. Mu 2004, boma la United Kingdom likapeleka ndalama zakukwana madola 180,000 ku boma la Namibia kuti lipeleke ndalama zakovwilira pa mulimo wa kunozga malo. Germany yapeleka ndalama zakukwana €1.1billion mu 2021 kwa vyaka 30 kuti yilute ku ŵanthu awo ŵakakomeka mu vyaka vya m'ma 1900, kweni ndalama izi zilute ku vinthu vyakuzenga, vyaumoyo, na masambiro, kuti zikagwirenge ntchito pa vinthu vya malo yayi.

Mu vyaru vinyake, ŵanthu ŵakughanaghana kuti vinthu viheni ivyo vikuchitika mu caru vingapangiska kuti ŵanthu ŵaleke kugwiliskira nchito vinthu ivi. Kweni ndalama izo zikufuma ku ŵanthu awo ŵakugwiliskira nchito vinthu ivi zikovwira kuti ŵanthu ŵaleke kusanga ndalama zinandi. Cimoza mwa vinthu ivyo vikukura comene mu caru ca Namibia ni malo ghakusungirako vinyama. Vinthu ivi ni vyakuzirwa comene ku ŵanthu awo ŵakukhala ku mizi, awo kanandi ŵakusoŵa nchito.

Mining and electricity

lembaMunda wa migodi ndiwo ukupeleka ndalama zinandi chomene ku charu cha Namibia. Namibia ni caru cacinayi pa vyaru ivyo vikupanga mafuta ghakununkhira mu Africa, ndipo pa vyaru vyose ivyo vikupanga uranium, ico cikaŵa cacinayi. Pali ndalama zinandi izo zaŵikika mu migodi ya uranium ndipo Namibia wakunozgekera kuti yiŵe charu chikuru icho chikufumiska uranium mu 2015. Ndipouli, mu chaka cha 2019, charu cha Namibia chikalutilira kupanga matani 750 gha uranium pa chaka, ndipo ichi chikapangiska kuti charu ichi chiŵe na vyakurya vinandi yayi pa charu chose chapasi.[122] Pakuti ku Namibia kuli malibwe ghanandi gha dayamondi, ndiko kukusangika malibwe gha mtengo wapatali comene. Nangauli charu cha Namibia chikumanyikwa kuti chili na malibwe gha dayamondi na uranium, kweni ŵanthu ŵakufumiskamo vinthu vinyake nga ni tungsten, golide, tin, fluorspar, manganese, marble, mkuŵa, na zinc. Mu nyanja ya Atlantic muli mafuta ghanandi agho ŵanthu ŵaghanaghanenge kughagura kunthazi. Kuyana na buku la "The Diamond Investigation", ilo likuyowoya za malonda gha dayamondi pa caru cose, kufuma mu 1978, De Beers, kampani yikuru comene ya dayamondi, yikaguranga dayamondi zinandi za ku Namibia, ndipo yikalutilira kucita nthena, cifukwa cakuti "ufumu uliwose uwo uzamwiza ku muwuso uzamukhumbikwira ndalama izi kuti uŵe na umoyo".

Vuto la magetsi m'nyumba ndi 220 V AC. Magesi ghakufumira ku malo ghakupangira magesi agho ghakupanga mphepo na maji. Nthowa zinyake zakupangira magesi nazo zikovwira. Mu 2010, boma la Namibia likakhumba kuzenga malo ghakugwilira nchito ya nyukiliya mu 2018. Ŵakapangaso ndondomeko yakuti pa malo agha paŵikikikenge vyakununkhira vya uranium.[123]

Diamonds

lembaNangauli malibwe ghanandi gha dayamondi ghakufuma ku Africa, kweni ku Namibia kulije nkhondo, kupoka, na kukoma ŵanthu nga umo viliri mu vyaru vinyake vya mu Africa. Vinthu ivi vikuchitika chifukwa cha umo vinthu viliri pa ndyali, umo chuma chiliri, masuzgo agho ŵanthu ŵakukumana nagho, umo vinthu viliri pa ndyali, kweniso chifukwa cha umo vinthu viliri mu vigaŵa vinyake.[124]

Oil and natural gas

lembaVikuwoneka kuti mu 2022, visimi viŵiri vya ku Orange vingaŵa na mafuta ghakukwana 2 biliyoni na 3 biliyoni. Ndalama izo ŵakulindizga kuti ŵazakasange zingawovwira kuti vinthu visinthe mu charu cha Namibia na kovwira kuti vinthu viŵe makora.[125]

Tourism

lembaNtchito zaulendo zikovwira comene (14.5%) pa GDP ya Namibia, ndipo zikupangiska nchito zinandi (18.2% za nchito zose) mwakudunjika panji mwakudunjika yayi, kweniso zikovwira ŵalendo ŵakujumpha miliyoni pa caka. Caru ici nchakudokeka comene mu Africa ndipo cikumanyikwa kuti ŵanthu ŵakuwona malo agho kuli vinyama na vinyama.

Ku malo agha kuli malo ghanandi agho ŵanthu awo ŵakukhumba kuwona malo ghakupambanapambana ŵakugona. Kusanga vyakurya na vyakurya vyakukhumbikwa pa ulendo wa ku Namibia ni vigaŵa vikuru na vyakukhora vya ndalama za ku Namibia. Mu 2000, vyakurya ivi vikawovwira kuti kuŵe na vyakurya vyakukhumbikwa pa ulendo wa ku Namibia.

Kweniso, maseŵero ghanyake ghakofya nga ni kujumpha mu maji, kuduka kufuma pasi, na kukwera galimoto ya 4x4 ghakumanyikwa chomene, ndipo mu misumba yinandi muli makampani agho ghakwendeska ŵanthu. Malo agho ŵanthu ŵanandi ŵakuluta ni Windhoek, Caprivi Strip, Fish River Canyon, Sossusvlei, Skeleton Coast Park, Sesriem, Etosha Pan na matawuni gha Swakopmund, Walvis Bay na Lüderitz.[126]

Windhoek ni malo ghakuzirwa chomene ku Namibia chifukwa cha malo agho ghakusangika kweniso chifukwa chakuti yili pafupi na Hosea Kutako International Airport. Malinga ndi kafukufuku wa The Namibia Tourism Exit Survey, omwe adapangidwa ndi Millennium Challenge Corporation ku Namibian Directorate of Tourism, 56% ya alendo onse omwe adapita ku Namibia mu 2012 ⁇ 13 adapita ku Windhoek. Maofesi ghanandi gha boma na mawupu agho ghakwendakwenda nga ni Namibia Wildlife Resorts na Namibia Tourism Board kweniso mabungwe agho ghakwendakwenda nga ni Hospitality Association of Namibia ghali na ofesi yawo yikuru ku Windhoek. Mu tawuni iyi muli malo ghanandi ghakukhala ŵanthu nga ni Windhoek Country Club Resort na malo ghanyake ghakukhala ŵanthu nga ni Hilton Hotels and Resorts.

Wupu wakuwona vya maulendo ku Namibia, wakuchemeka kuti Namibia Tourism Board (NTB), ukakhazikiskika na dango la chalo cha Namibia la 2000 (Act 21 of 2000). Chilato chake nchakuti boma liŵikenge malango ghakwendeskera vyamwendekero ndiposo kuti Namibia yiŵe malo ghakwendera vyamwendekero. Ku Namibia kuli mabungwe ghanandi agho ghakwendakwenda, nga ni Federation of Namibia Tourism Associations (bungwe ilo likwimira mabungwe ghose agho ghakwendakwenda), Hospitality Association of Namibia, Association of Namibian Travel Agents, Car Rental Association of Namibia na Tour and Safari Association of Namibia.

Water supply and sanitation

lembaKu Namibia, maji ghakukwana ghakupelekeka na kampani ya NamWater, iyo yikuguliska maji ku matawuni agho ghakuguliska maji kwizira mu magesi. Mu vigaŵa vya ku mizi, Dipatimenti Yakupeleka Maji ku Vigaŵa vya ku Mizi mu Unduna wa vya Vyakurya, Vyakumwa na Vyamuthengere ndiyo yikupanga maji ghakumwa.

Mu 2011, wupu wa UN ukawona kuti kufuma waka apo charu cha Namibia chikamba kujiwusa mu 1990, maji ghakwenda makora chomene. Kweni ŵanthu ŵanandi ŵakutondeka kugwiliskira nchito maji agha cifukwa cakuti ghalije nchito ndiposo cifukwa cakuti malo ghakusungiramo maji ghali kutali comene na ku mizi. Lekani ŵanthu ŵanandi ŵa ku Namibia ŵakutemwa visimi vya mu mphepete mwa nyanja m'malo mwa visimi vya maji ivyo vili kutali.[127]

Kuyana na umo ŵanthu ŵakucitira kuti ŵaŵe na maji ghawemi, mu Namibia mulije maji ghawemi. Pa sukulu izi pali masukulu 298 agho ghalije vimbuzi. Pafupifupi ŵana 50 pa 100 awo ŵakufwa, ŵakufwa cifukwa ca kusoŵa maji ghawemi, malo ghawemi ghakusungira vyakurya, panji cifukwa ca kulwaralwara; ndipo 23 pa 100 ŵakufwa cifukwa ca kusulura pera. Wupu wa UN ukayowoya kuti mu caru ici muli "kusoŵa maji".

Ku vigaŵa vinandi, nyumba za ŵanthu ŵakuzirwa na ŵanthu ŵapakati ndizo zikukhalanga makora yayi. Vipinda vya ŵanthu ŵekha ni vyakudura comene ku ŵanthu wose mu matawuni cifukwa ca maji agho ŵakugwiliskira nchito na ndalama izo ŵakugwiliskira nchito pakuvizenga. Pa vigaŵa vya ku mizi, ŵanthu 13 pa ŵanthu 100 ŵali na maji ghawemi, apo mu 1990 ŵanthu 8 pera ndiwo ŵakaŵa na maji ghawemi. Ŵanandi awo ŵakukhala ku Namibia ŵakugwiliskira nchito "vipinda vyamumphepete", ivyo ni mathumba gha pulasitiki agho ŵakugwiliskira nchito para ŵakukhumba kukazuzga, ndipo para ŵaghagwiliskira nchito ŵakughataya mu thengere. Kugwiliskira nchito malo ghambura kuvunduka pafupi na malo ghakukhalamo kuti munthu wanjiremo na kukhalamo ni suzgo likuru ku ŵanthu.[128]

Demographics

lembaPa vyaru vyose ivyo vili na wanangwa wakujiwusa, Namibia ndiyo yili na ŵanthu ŵachoko chomene, kufuma pa Mongolia. Mu 2017 ŵanthu ŵakaŵapo pafupifupi 3.08 pa km2. Kuyana na UN, mu 2015 mwanakazi yumoza wakababanga ŵana 3.47.[129]

Ethnic groups

lembaŴanandi mwa ŵanthu ŵa ku Namibia ŵakuyowoya ciyowoyero ca Bantu, comenecomene ŵa fuko la Ovambo, ilo ni hafu ya ŵanthu wose ŵa ku Namibia, ndipo ŵakukhala kumpoto kwa caru ici. Mitundu yinyake ni Herero na Himba, awo ŵakuyowoya ciyowoyero cakuyana na ici, na Damara, awo ŵakuyowoya ciyowoyero ca Khoekhoe nga ni Nama.

Padera pa ŵantu ŵa mtundu wa Bantu, paliso magulu ghanandi gha ŵanthu ŵa mtundu wa Khoisan (nga ni Nama na San), awo mbana ŵa ŵanthu ŵa ku Southern Africa. Kweniso mu caru ici muli ŵanthu ŵanyake awo ŵakacimbira ku Angola. Paliso magulu ghaŵiri gha ŵanthu ŵamitundu yakupambanapambana, awo ŵakucemeka kuti "Coloureds" na "Basters", ndipo wose pamoza ŵali na ciŵelengero ca 8.0% (ŵanthu ŵa mitundu yakupambanapambana ŵakuluska ŵa mitundu yakupambanapambana). Ku Namibia kuli ŵanthu ŵanandi ŵa ku China, ndipo mu 2006 ŵanthu aŵa ŵakaŵa 40,000.[130]

Ŵazungu (ŵakufuma ku Afrika, Germany, Britain na Portugal) ŵali pakati pa 4.0 na 7.0% mwa ŵanthu wose. Nangauli ciŵelengero ca ŵanthu aŵa cikakhira pamasinda pa kupokera wanangwa cifukwa ca kufumako ku vyaru vinyake ndiposo cifukwa ca kucepa kwa ŵana awo ŵakubabika, kweni ŵacali kuŵa ŵaciŵiri pa ŵanthu ŵa ku Europe, mu viŵelengero vyawo na viŵelengero vyawo, mu vyaru vya kumwera kwa Sahara (pamanyuma pa South Africa).[131] Ŵazungu ŵanandi ŵa ku Namibia na ŵanthu ŵanyake ŵa mitundu yakupambanapambana ŵakuyowoya ciyowoyero ca Afrikaans ndipo ŵali na mitheto yakuyana na ya ŵanthu ŵa ku South Africa. Ŵazungu ŵanandi (pafupifupi 30,000) ŵali kufuma ku ŵa German awo ŵakakhalanga ku Namibia pambere ŵandambe kuwukira caru ca South Africa pa Nkhondo Yakwamba ya Caru Cose, ndipo ŵali na masukulu na masukulu gha ku Germany. Pafupifupi ŵanthu wose ŵa ku Portugal awo ŵakakhalanga mu caru ici ŵakafuma ku Angola, uko kale kukaŵa caru ca Portugal. Mu 1960, ku South-West Africa kukaŵa ŵanthu 526,004, ndipo 73,464 ŵakaŵa ŵazungu (14 peresenti).[132]

Censuses

lembaKu Namibia, pakuŵa kalembera wa ŵanthu para pajumpha vilimika khumi. Ŵakati ŵaŵa na wanangwa, ŵakalemba ŵanthu na nyumba zawo mu 1991. Ŵakalembaso mu 2001, 2011, na 2023 (ŵakacedwa vyaka viŵiri cifukwa ca nthenda ya COVID-19 kweniso cifukwa ca suzgo la ndalama). Nthowa yakupimira ni kupenda ŵanthu wose awo ŵakukhala mu Namibia pa zuŵa ilo ŵakalembeka, kulikose uko ŵakukhala. Nthowa iyi yikucemeka de facto. Kuyana na ndondomeko ya kalembera iyi, caru ici cagaŵika mu vigaŵa 4,042. Malo agha ghakupambana yayi na mphaka za malo ghakusankhirapo kuti ŵasange fundo zakugomezgeka zakukhwaskana na mavoti.

Mu 2011, ŵanthu ŵakakwana 2,113,077. Pakati pa 2001 na 2011 chiŵelengero cha ŵanthu icho chikakwera chaka chilichose chikaŵa 1.4%, kuyana na 2.6% mu vyaka 10 vyakumasinda.[133]

Urban settlements

lembaKu Namibia kuli matawuni 13, agho ghakulamulirwa na ma municipalities na matawuni 26, agho ghakulamulirwa na town councils.[134][135] Windhoek, uwo ni msumba ukuru, ndiwo ni msumba ukuru comene mu Namibia.

| Mndandanda | Region | Ŵanthu | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Windhoek Rundu |

1 | Windhoek | Khomas | 325,858 | Walvis Bay Swakopmund | ||||

| 2 | Rundu | Kavango | 63,431 | ||||||

| 3 | Walvis Bay | Erongo | 62,096 | ||||||

| 4 | Swakopmund | Erongo | 44,725 | ||||||

| 5 | Oshakati | Oshana | 36,541 | ||||||

| 6 | Rehoboth | Hardap | 28,843 | ||||||

| 7 | Katima Mulilo | Zambezi | 28,362 | ||||||

| 8 | Otjiwarongo | Otjozondjupa | 28,249 | ||||||

| 9 | Ondangwa | Oshana | 22,822 | ||||||

| 10 | Okahandja | Otjozondjupa | 22,639 | ||||||

Religion

lembaŴanthu ŵanandi ku Namibia Mbakhristu, ndipo pafupifupi 75 pa ŵanthu 100 ŵaliwose ni Mapulotesitanti, ndipo 50 pa ŵanthu 100 ŵaliwose ni Malutere. Ŵanthu ŵa chisopa cha Lutheran ndiwo mbachoko chomene mu charu ichi, ndipo ŵali kufuma ku ŵanthu ŵa ku Germany na ŵa ku Finland awo ŵakambiska visopa ivi mu nyengo iyo charu ichi chikaŵa pasi pa Britain.

Mu virimika vya m'ma 1800, ŵamishonale ŵakayamba nchito ya kupharazga, ndipo ŵanthu ŵanandi ŵa ku Namibia ŵakamba kuŵa Ŵakhristu. Mazuŵa ghano, Ŵakhristu ŵanandi mba Lutheran, kweni paliso Ŵakatolika ŵa Roma, ŵa Methodist, ŵa Anglican, ŵa African Methodist Episcopal, ŵa Dutch Reformed, ŵa Latter-day Saints, na Ŵakaboni ŵa Yehova.

Ŵanandi mwa ŵanthu aŵa mba Nama, ndipo ŵalipo pafupifupi 9,000. Ku Namibia kuli Ŵayuda ŵacoko waka pafupifupi 100.[137]

Languages

lembaM'paka mu 1990, Cingelezi, Cijeremani, na Cifrikaans zikaŵa viyowoyero vya boma. Pambere caru ca Namibia cindafumeko ku South Africa, gulu la SWAPO likagomezganga kuti caru ici cikwenera kuŵa na ciyowoyero cimoza, ndipo likapambananga na caru ca South Africa (co cikapeleka mazaza ku viyowoyero vikuruvikuru vyose 11 vya mu caru ici), ico cikati "nthowa ya kusankhana mitundu na viyowoyero yikamanyikwa makora". Mwantheura, wupu wa SWAPO ukasora Cingelezi kuŵa ciyowoyero ca boma, nangauli ŵanthu pafupifupi 3 pa ŵanthu 100 ŵaliwose ndiwo ŵakuyowoya Cingelezi. Ndondomeko iyi yikugwira nchito pa nchito za boma, masambiro na pa wayilesi, comenecomene pa wayilesi ya boma ya NBC.[138] Viyowoyero vinyake vya mu vyaru ivi vyazomerezgeka kusambizgika mu masukulu gha pulayimale. Masukulu ghapadera ghakwenera kulondezga fundo zakuyana waka na za boma, ndipo "Chingelezi" ni sambiro lakucicizgika. Ŵanthu ŵanyake ŵakususka kuti, nga umo vikaŵira mu vyaru vinyake vya mu Africa, ŵanthu ŵanandi ŵakuluta ku sukulu za chiyowoyero chimoza. Ŵanthu ŵanandi ŵakuluta ku sukulu za chiyowoyero chimoza.

Kuyana na census ya mu 2011, viyowoyero ivyo vikuyowoyeka chomene ni Oshiwambo (chiyowoyero icho chikuyowoyeka na ŵanthu ŵanandi mu nyumba 49%), Khoekhoegowab (11.3%), Afrikaans (10.4%), RuKwangali (9%), na Otjiherero (9%). Ciyowoyero ico ŵanthu ŵanandi ŵakucimanya ni ciyowoyero ca Afrikaans, ico cikuyowoyeka mu caru ici. Viyowoyero vyose viŵiri, Cingelezi na Ciafrikaans, vikuyowoyeka pa caru cose. Kuyana na census ya mu chaka cha 2011, viyowoyelo vyose ivyo vikuyowoyeka ni 48.9% Oshiwambo, 11.3% Khoekhoegowab, 10.4% Afrikaans, 8.6% Otjiherero, 8.5% RuKwangali, 4.8% siLozi, 3.4% English, 1.2% Other African languages, 0.9% German, 0.8% San, 0.7% Other European languages, 0.3% Setswana, and 0.1% Asian languages.

Ŵazungu ŵanandi ŵakuyowoya ciyowoyero ca Afrikaans panji Cigerman. Pakati pajumpha vilimika vyakujumpha 100 kufuma apo boma la Germany likamalira kulamulira caru ici, ciyowoyero ca Cijeremani cikulutilira kuŵa cakovwira comene pa malonda. Afrikaans yikuyowoyeka na 60% ya ŵazungu, German na 32%, English na 7% ndipo Portuguese na 4 ⁇ 5%. Pakuti charu ichi chili pafupi chomene na Angola, ŵanthu ŵanandi ŵakuyowoya Chiphwitikizi.[139]

Health

lembaMu 2017 ŵanthu ŵakakhala na umoyo vyaka 64, ndipo ichi ntchigaŵa cha ŵanthu ŵachoko chomene pa charu chose.

Mu 2012, boma la Namibia likambiska pulogiramu ya National Health Extension Program. Mu pulogiramu iyi mukaŵa ŵanthu ŵakukwana 1,800 (2015), ndipo ŵanthu aŵa ŵakasambizgika umo ŵangapwelelera umoyo wawo kwa myezi 6. Mu pulogiramu iyi mukaŵaso ntchito ya kovwira ŵalwari, kupwelelera umoyo wawo, kupwelelera maji, kupwelelera umoyo wawo, kupima HIV, na kupwelelera ŵanthu awo ŵali na majeremusi.

Namibia yikukumana na nthenda zakwambukira yayi. Kafukufuku wa Demographic and Health (2013) wakulongosora ivyo ŵasanga pa nkhani ya kuthamanga kwa ndopa, kuthamanga kwa ndopa, nthenda ya shuga, na kunenepa chomene:[140]

- Among eligible respondents age 35–64, more than 4 in 10 women (44 percent) and men (45 percent) have elevated blood pressure or are currently taking medicine to lower their blood pressure.

- Forty-nine percent of women and 61 percent of men are not aware that they have elevated blood pressure.

- Forty-three percent of women and 34 percent of men with hypertension are taking medication for their condition.

- Only 29 percent of women and 20 percent of men with hypertension are taking medication and have their blood pressure under control.

- Six percent of women and 7 percent of men are diabetic; that is, they have elevated fasting plasma glucose values or report that they are taking diabetes medication. An additional 7 percent of women and 6 percent of men are prediabetic.

- Sixty-seven percent of women and 74 percent of men with diabetes are taking medication to lower their blood glucose.

- Women and men with a higher-than-normal body mass index (25.0 or higher) are more likely to have elevated blood pressure and elevated fasting blood glucose.[141]

| ██ 15–50 |

Nthenda ya HIV yikulutilira kuŵa suzgo likuru ku Namibia nangauli Unduna wa vya Umoyo na Wovwiri pa vya Umoyo wa Ŵanthu wachita vinandi pa nkhani ya kovwira ŵanthu awo ŵali na nthenda iyi. Mu 2001, ŵanthu pafupifupi 210,000 ŵakaŵa na HIV/AIDS, ndipo ciŵelengero ca awo ŵakafwa mu 2003 cikaŵa 16,000. Kuyana na lipoti la UNAIDS la mu 2011, nthenda iyi mu Namibia "yikuwoneka kuti yikumara". Pakuti nthenda ya HIV/AIDS yacepeska ŵanthu awo ŵakugwira nchito, ciŵelengero ca ŵana ŵambura ŵapapi cikusazgikira. Boma ndilo likwenera kusambizga ŵana aŵa, kuŵapa cakurya, nyumba na vyakuvwara. Kafukufuku wakukhwaskana na umo ŵanthu ŵakukhalira na umoyo wawo, uyo wali na kachilombo ka HIV wakamara mu 2013 ndipo ukaŵa kachinayi pa kafukufuku wakukhwaskana na umo ŵanthu ŵakukhalira na umoyo wawo mu charu chose cha Namibia. DHS yikayowoya vinthu vyakuzirwa ivyo vikuchitika para ŵanthu ŵali na HIV:

- Overall, 26 percent of men age 15–49 and 32 percent of those age 50–64 have been circumcised. HIV prevalence for men age 15–49 is lower among circumcised (8.0 percent) than among uncircumcised men (11.9 percent). The pattern of lower HIV prevalence among circumcised than uncircumcised men is observed across most background characteristics. For each age group, circumcised men have lower HIV prevalence than those who are not circumcised; the difference is especially pronounced for men age 35–39 and 45–49 (11.7 percentage points each). The difference in HIV prevalence between uncircumcised and circumcised men is larger among urban than rural men (5.2 percentage points versus 2.1 percentage points).

- HIV prevalence among respondents age 15–49 is 16.9 percent for women and 10.9 percent for men. HIV prevalence rates among women and men age 50–64 are similar (16.7 percent and 16.0 percent, respectively).

- HIV prevalence peaks in the 35–39 age group for both women and men (30.9 percent and 22.6 percent, respectively). It is lowest among respondents age 15–24 (2.5–6.4 percent for women and 2.0–3.4 percent for men).

- Among respondents age 15–49, HIV prevalence is highest for women and men in Zambezi (30.9 percent and 15.9 percent, respectively) and lowest for women in Omaheke (6.9 percent) and men in Ohangwena (6.6 percent).

- In 76.4 percent of the 1,007 cohabiting couples who were tested for HIV in the 2013 NDHS, both partners were HIV negative; in 10.1 percent of the couples, both partners were HIV positive; and 13.5 percent of the couples were discordant (that is, one partner was infected with HIV and the other was not).[141]

Mu 2015, Unduna wa vya Umoyo na Wovwiri ku Ŵana na UNAIDS ukalemba lipoti la umo matenda gha HIV ghakuthandazgikira mu ŵanthu ŵa vyaka 15 kufika 49, ndipo likati ŵanthu pafupifupi 210,000 ŵakukhala na HIV.

Suzgo ya maleriya yikuwoneka kuti yikusazgikira cifukwa ca nthenda ya AIDS. Kafukufuku wakulongora kuti ku Namibia, para munthu wali na HIV, wakulwaraso maleriya pafupifupi 14.5 peresenti. Kweniso para munthu wali na HIV, wakufwa na maleriya pafupifupi pa nyengo yimoza. Mu 2002 mu caru ici mukaŵa ŵadokotala 598 pera.[143]

Mwambo

lembaSport

lembaMaseŵero ghakumanyikwa comene mu Namibia ni mpira. Timu ya mpira ya ku Namibia yikaluta ku Africa mu 1998, 2008 na 2019, kweni yichali yayi ku World Cup.

Timu ya rugby ya ku Namibia ndiyo yikwenda makora comene pa nkhonyo zose, ndipo yalutapo pa nkhonyo zinkhondi na yimoza ya caru cose. Mu 1999, 2003, 2007, 2011, 2015 na 2019 Namibia yikaŵapo pa mpikisano wa Rugby World Cup. Charu cha India chikupanga maseŵero ghakupambanapambana, nga ni maseŵero gha Cricket World Cup 2003, ICC T20 World Cup 2021 na ICC Men's T20 World Cup 2022. Mu Disembala 2017, Namibia Cricket yikafika pa final ya Cricket South Africa (CSA) Provincial One Day Challenge kwa nyengo yakwamba.[144] Mu Febuluwale 2018 ku Zimbabwe kukachitika chiphikiro cha ICC World Cricket League Division 2 icho chikachitikanga na Namibia, Kenya, UAE, Nepal, Canada na Oman. Kweniso Namibia yikafika pa malo ghakwenelera kuti yilute ku ICC T20 World Cup 2021 ndipo yikaluta ku Super 12.

Munthu wakumanyikwa comene wa ku Namibia ni Frankie Fredericks, uyo wakucimbilira mtunda wa mamita 100 na 200. Wakawina mendulo zinayi za siliva pa maseŵero gha Olimpiki (1992, 1996) ndipo wali na mendulo zinandi pa maseŵero gha pa caru cose gha maseŵero ghakukhozga thupi. Trevor Dodds ndiyo wakawina mpikisano wa Greater Greensboro Open mu 1998, ndipo uwu ukaŵa mpikisano umoza mwa mipikisano 15 iyo wakachitapo pa umoyo wake. Mu 1998, wakaŵa pa nambara 78 pa caru cose. Dan Craven wakayimira Namibia pa maseŵero gha Olimpiki gha 2016 mu mpikisano wa pa msewu na mpikisano wa munthu payekha. Boxer Julius Indongo ni mulongozgi wa WBA, IBF, na IBO mu gulu la light welterweight. Munthu munyake wakumanyikwa comene wa ku Namibia ni Jacques Burger, uyo kale wakaseŵeranga rugby. Burger wakaseŵera mu timu ya Saracens na Aurillac ku Europe, kweniso wakaseŵera mu timu ya caru cose ya Spain maulendo 41.

Media

lembaNangauli caru ca Namibia cili na ŵanthu ŵacoko waka, kweni pali vinthu vinandi ivyo ŵanthu ŵakuyowoya. Pali ma TV ghaŵiri, mawayilesi 19 (kwambura kupenderako mawayilesi gha ŵanthu wose), na manyuzipepara 5 gha zuŵa na zuŵa, kweniso magazini ghanandi gha sabata yiliyose. Kweniso pali nkhani zinandi izo zikufuma ku vyaru vinyake, comenecomene ku South Africa. Ŵapharazgi ŵa pa Intaneti ŵakugwiliskira nchito mabuku ghakupulintira. Boma la Namibia lili na wupu wakulemba nkhani wakucemeka NAMPA. Ŵapharazgi pafupifupi 300 ŵakugwira nchito mu caru ici.

Nyuzipepara yakwamba ya ku Namibia yikaŵa Windhoeker Anzeiger ya ciyowoyero ca Cijeremani, iyo yikamba mu 1898. Mu nyengo ya kuwusa kwa Germany, manyuzipepara ghakalongosoranga comene ivyo vikacitikanga nadi ndiposo maghanoghano gha ŵazungu awo ŵakayowoyanga Cigerman. Ŵazungu ŵanandi ŵakaŵayuyuranga panji ŵakaŵawonanga kuti mbakofya. Mu nyengo ya boma la South Africa, ŵanthu ŵacisungu ŵakalutilira kuŵa na maghanoghano ghambura kwenelera, ndipo boma la Pretoria likalutilira kuŵa na nkhongono pa nkhani za nyuzipepara za ku South West Africa. Ŵapharazgi ŵa nyuzipepara ŵakawonekanga nga kuti ŵakutimbanizga wupu uwo ukaŵako, ndipo kanandi ŵakawofyanga ŵanthu awo ŵakasuskanga boma.[145][146][147]

Manyuzipepara gha mazuŵa ghano ni The Namibian (Chingelezi na viyowoyero vinyake), Die Republikein (Chiafrikaans), Allgemeine Zeitung (Chijeremani) na Namibian Sun (Chingelezi) kweniso New Era (Chingelezi). Kupatulapo nyuzipepara yikuru ya The Namibian, iyo yili na ŵanthu awo ŵakugomezga, nyuzipepara zinyake izo zili mu gulu la Democratic Media Holdings. Ŵapharazgi ŵanyake awo ŵakulembeka mu manyuzipepara ni: Informanté, la TrustCo, Windhoek Observer, Namibia Economist, na Namib Times. Mu magazini ya Current Affairs muli mabuku nga ni Insight Namibia, Vision2030 Focus magazine na Prime FOCUS. Magazini ya Sister Namibia ndiyo yikugwira nchito kwa nyengo yitali mu Namibia, ndipo magazini ya Namibia Sport ndiyo yikupharazga vya maseŵero pa caru cose. Kweniso, mabuku ghakusindikizgika ghakulembeka na gulu la chipani, nyuzipepara za ŵana ŵa sukulu, na mabuku ghakuyowoya vya ŵanthu.

Wayilesi yikamba mu 1969, ndipo TV yikamba mu 1981. Mulimo wa pa wayilesi na wa pa wayilesi lero ukucitika na wupu wa boma wa Namibia Broadcasting Corporation (NBC). Wupu uwu ukupeleka wayilesi ya TV na wayilesi ya "National Radio" mu Cingelezi na viyowoyero vinyake 9. Masiteshoni gha pa wayilesi ghakukwana 9 ghakupharazga comene Cingelezi, kupaturako Radio Omulunga (Oshiwambo) na Kosmos 94.1 (Afrikaans). TV ya One Africa yakhala ikulimbana ndi NBC kuyambira m'ma 2000.[145][148]

Kuyana na vyaru vyapafupi, ku Namibia kuli wanangwa wakuyowoya na ŵanthu. Mu vyaka vyakumasinda, caru ici cikaŵanga pa malo ghapacanya pa mapulogiramu gha Reporters Without Borders ghakulongosora vya wanangwa wa ŵanthu wakulemba nkhani. Mu 2010, cikaŵa pa malo gha 21. Kafukufuku wakukhwaskana na vyakupharazga ku Africa wakulongora kuti vinthu vili makora. Ndipouli, nga ni umo viliri mu vyaru vinyake, mu Namibia ŵimiliri ŵa boma na ŵamalonda ŵakulutilira kuŵa na mazaza pa nkhani ya nkhani za nyuzipepara. Mu 2009, boma la Namibia likaŵa pa malo gha 36 pa nkhani ya wanangwa wa ŵanthu wakuyowoyapo. Mu 2013 yikaŵa pa malo 19, mu 2014 yikaŵa pa malo 22 ndipo mu 2019 yikaŵa pa malo 23. Ichi chikung'anamura kuti sono ni charu icho chili pa malo ghapachanya chomene pa vyaru vya mu Africa pa nkhani ya wanangwa wa ŵanthu wakuyowoya.

Ŵapharazgi na manyuzipepara ku Namibia ŵakwimikika na chaputara cha ku Namibia cha Media Institute of Southern Africa na Editors' Forum of Namibia. Mu 2009, boma likasora munthu wakujiyimira payekha kuti waŵavikilire.[145]

Education

lembaKu Namibia kuli masambiro gha mahala gha pulayimale na gha sekondale. Ŵana ŵa sukulu ŵa giredi 1 kufika ku 7 ni awo ŵali mu kilasi la pulayimale, ndipo ŵana ŵa sukulu ŵa giredi 8 kufika ku 12 ni awo ŵali mu kilasi la sekondare. Mu 1998, ku Namibia kukaŵa ŵana 400,325 ŵa sukulu za pulayimale na 115,237 ŵa sukulu za sekondare. Mu 1999, chiŵerengero cha ŵana ŵa sukulu na ŵasambizgi chikaŵa 32:1, ndipo pafupifupi 8% ya GDP yikagwiranga nchito pa masambiro. Mulimo wakunozga visambizgo, kafukufuku wa masambiro, na kusambizga ŵasambizgi ukuchitika na National Institute for Educational Development (NIED) ku Okahandja.[149] Pa vyaru vya kumwera kwa Sahara, caru ca Namibia nchimoza mwa vyaru ivyo vili na ŵanthu ŵanandi comene awo ŵakumanya kuŵazga na kulemba. Kuyana na CIA World Factbook, mu 2018 ŵanthu 91.5% ŵa vyaka 15 kuya munthazi ŵakumanya kuŵazga na kulemba.

Masukulu ghanandi ku Namibia ghakupharazgika na boma, kweni ghanyake ni ghapadera. Masukulu agha ghakukolerana na masambiro gha mu caru ici. Pali masukulu ghanayi ghakusambizga ŵasambizgi, masukulu ghatatu gha vya ulimi, na masukulu gha polisi. Masukulu agha ni: University of Namibia (UNAM), International University of Management (IUM) na Namibia University of Science and Technology (NUST). Namibia yikaŵa pa malo gha 100 pa Global Innovation Index mu 2021.[150][151][152][153][154]

Wonaniso

lembaUkaboni

lembaNotes

lemba- ↑ "Communal Land Reform Act, Afrikaans" (PDF). Government of Namibia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 Febuluwale 2016. Retrieved 18 Febuluwale 2016.

- ↑ "Communal Land Reform Act, German" (PDF). Government of Namibia. Retrieved 18 Febuluwale 2016. [permanent dead link]

- ↑ "Communal Land Reform Act, Khoekhoegowab" (PDF). Government of Namibia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 Febuluwale 2016. Retrieved 18 Febuluwale 2016.

- ↑ "Communal Land Reform Act, Otjiherero" (PDF). Government of Namibia. Retrieved 18 Febuluwale 2016. [permanent dead link]

- ↑ "Communal Land Reform Act, Oshiwambo" (PDF). Government of Namibia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 Malichi 2016. Retrieved 18 Febuluwale 2016.

- ↑ "Communal Land Reform Act, Rukwangali" (PDF). Government of Namibia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 Febuluwale 2016. Retrieved 18 Febuluwale 2016.

- ↑ "Communal Land Reform Act, Setswana" (PDF). Government of Namibia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 Febuluwale 2016. Retrieved 18 Febuluwale 2016.

- ↑ "Communal Land Reform Act, Lozi" (PDF). Government of Namibia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 Febuluwale 2016. Retrieved 18 Febuluwale 2016.

- ↑ Longola ivyo vyabudika: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedDual - ↑ "Namibia". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 22 Juni 2023.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 24 Epulelo 2023.

- ↑ "GINI index (World Bank estimate)". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 20 Janyuwale 2019.

- ↑ "Human Development Report 2021/2022" (PDF) (in English). United Nations Development Programme. 8 Sekutembala 2022. Retrieved 8 Sekutembala 2022.

- ↑ Wells, John C. (2008), Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.), Longman, ISBN 978-1405881180

- ↑ Roach, Peter (2011), Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521152532

- ↑ Peter Shadbolt (24 Okutobala 2012). "Namibia country profile: moving on from a difficult past". CNN.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Spriggs, A. (2001) Template:WWF ecoregion

- ↑ "The Man Who Named Namibia- Mburumba Kerina". The Namibian. Retrieved 15 Juni 2021.

- ↑ Belda, Pascal (Meyi 2007). Namibia (in English). MTH Multimedia S.L. ISBN 978-84-935202-1-2.

- ↑ Dierks, Klaus. "Biographies of Namibian Personalities, A". Archived from the original on 15 Okutobala 2008. Retrieved 24 Juni 2010.

- ↑ Dierks, Klaus. "Warmbad becomes two hundred years". Klausdierks.com. Archived from the original on 21 Ogasiti 2019. Retrieved 22 Juni 2010.

- ↑ Vedder 1997, p. 177.

- ↑ Vedder 1997, p. 659.

- ↑ Observador. "Padrão português com 500 anos foi roubado da Namíbia no século XIX. Vai ser devolvido". Observador (in European Portuguese). Retrieved 7 Disembala 2020.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 "Namibia 30 vuotta – Suomalaisilla oli merkittävä rooli Namibian itsenäistymisessä" (in Finnish). Finnish Evangelical Lutheran Mission. 20 Malichi 2020. Retrieved 11 Febuluwale 2023.

- ↑ "German South West Africa". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 15 Epulelo 2008.

- ↑ Lechler, Marie; McNamee, Lachlan (Disembala 2018). "Indirect Colonial Rule Undermines Support for Democracy: Evidence From a Natural Experiment in Namibia". Comparative Political Studies (in English). 51 (14): 1864–1871 (p. 7–14). doi:10.1177/0010414018758760. ISSN 0010-4140. S2CID 158335936. Archived from the original on 15 Meyi 2023. Retrieved 2 Juni 2023.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ↑ Lechler, Marie; McNamee, Lachlan (Disembala 2018). "Indirect Colonial Rule Undermines Support for Democracy: Evidence From a Natural Experiment in Namibia". Comparative Political Studies (in English). 51 (14): 1865 (p. 8). doi:10.1177/0010414018758760. ISSN 0010-4140. S2CID 158335936. Archived from the original on 15 Meyi 2023. Retrieved 2 Juni 2023.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ↑ David Olusoga (18 Epulelo 2015). "Dear Pope Francis, Namibia was the 20th century's first genocide". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 Novembala 2015.

- ↑ Drechsler, Horst (1980). The actual number of deaths in the limited number of battles with the Germany Schutztruppe (expeditionary force) were limited; most of the deaths occurred after fighting had ended. The German military governor Lothar von Trotha issued an explicit extermination order, and many Herero died of disease and abuse in detention camps after being taken from their land. A substantial minority of Herero crossed the Kalahari desert into the British colony of Bechuanaland (modern-day Botswana), where a small community continues to live in western Botswana near to border with Namibia. Let us die fighting, originally published (1966) under the title Südwestafrika unter deutscher Kolonialherrschaft. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag.

- ↑ Adhikari, Mohamed (2008). "'Streams of Blood And Streams of Money': New Perspectives on the Annihilation of the Herero and Nama Peoples of Namibia, 1904–1908". Kronos. 34 (34): 303–320. JSTOR 41056613.

- ↑ Madley, Benjamin (2005). "From Africa to Auschwitz: How German South West Africa Incubated Ideas and Methods Adopted and Developed by the Nazis in Eastern Europe". European History Quarterly. 35 (3): 429–464. doi:10.1177/0265691405054218. S2CID 144290873. says it influenced Nazis.

- ↑ Kößler, Reinhart; Melber, Henning (2004). "Völkermord und Gedenken: Der Genozid an den Herero und Nama in Deutsch-Südwestafrika 1904–1908". Jahrbuch zur Geschichte und Wirkung des Holocaust [Genocide and memory: the genocide of the Herero and Nama in German South-West Africa, 1904–08] (in German). pp. 37–75. ISBN 9783593372822.

- ↑ Andrew Meldrum (15 Ogasiti 2004). "German minister says sorry for genocide in Namibia". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 Okutobala 2018.

- ↑ [Völkermord an Herero und Nama: Abkommen zwischen Deutschland und Namibia "German minister says sorry for genocide in Namibia"]. bpb. 22 Juni 2021. Retrieved 24 Janyuwale 2023.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - ↑ 36.0 36.1 Rajagopal, Balakrishnan (2003). International Law from Below: Development, Social Movements and Third World Resistance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 50–68. ISBN 978-0521016711.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Louis, William Roger (2006). Ends of British Imperialism: The Scramble for Empire, Suez, and Decolonization. London: I.B. Tauris & Company, Ltd. pp. 251–261. ISBN 978-1845113476.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 38.3 Vandenbosch, Amry (1970). South Africa and the World: The Foreign Policy of Apartheid. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky. pp. 207–224. ISBN 978-0813164946.

- ↑ First, Ruth (1963). Segal, Ronald (ed.). South West Africa. Baltimore: Penguin Books, Incorporated. pp. 169–193. ISBN 978-0844620619.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Crawford, Neta (2002). Argument and Change in World Politics: Ethics, Decolonization, and Humanitarian Intervention. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 333–336. ISBN 978-0521002790.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 Herbstein, Denis; Evenson, John (1989). The Devils Are Among Us: The War for Namibia. London: Zed Books Ltd. pp. 14–23. ISBN 978-0862328962.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Müller, Johann Alexander (2012). The Inevitable Pipeline Into Exile. Botswana's Role in the Namibian Liberation Struggle. Basel, Switzerland: Basler Afrika Bibliographien Namibia Resource Center and Southern Africa Library. pp. 36–41. ISBN 978-3905758290.

- ↑ Kangumu, Bennett (2011). Contesting Caprivi: A History of Colonial Isolation and Regional Nationalism in Namibia. Basel: Basler Afrika Bibliographien Namibia Resource Center and Southern Africa Library. pp. 143–153. ISBN 978-3905758221.

- ↑ Moorsom, Richard (Epulelo 1979). "Labour Consciousness and the 1971–72 Contract Workers Strike in Namibia". Development and Change. 10 (2): 205–231. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7660.1979.tb00041.x.

- ↑ Herbstein, Denis; Evenson, John (1989). The Devils Are Among Us: The War for Namibia. London: Zed Books Ltd. pp. 14–23. ISBN 978-0862328962.

- ↑ Dobell, Lauren (1998). Swapo's Struggle for Namibia, 1960–1991: War by Other Means. Basel: P. Schlettwein Publishing Switzerland. pp. 27–39. ISBN 978-3908193029.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 Yusuf, Abdulqawi (1994). African Yearbook of International Law, Volume I. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. pp. 16–34. ISBN 978-0-7923-2718-9.

- ↑ Peter, Abbott; Helmoed-Romer Heitman; Paul Hannon (1991). Modern African Wars (3): South-West Africa. Osprey Publishing. pp. 5–13. ISBN 978-1-85532-122-9.[permanent dead link]

- ↑ Williams, Christian (Okutobala 2015). National Liberation in Postcolonial Southern Africa: A Historical Ethnography of SWAPO's Exile Camps. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 73–89. ISBN 978-1107099340.

- ↑ Hughes, Geraint (2014). My Enemy's Enemy: Proxy Warfare in International Politics. Brighton: Sussex Academic Press. pp. 73–86. ISBN 978-1845196271.

- ↑ Bertram, Christoph (1980). Prospects of Soviet Power in the 1980s. Basingstoke: Palgrave Books. pp. 51–54. ISBN 978-1349052592.

- ↑ Vanneman, Peter (1990). Soviet Strategy in Southern Africa: Gorbachev's Pragmatic Approach. Stanford: Hoover Institution Press. pp. 41–57. ISBN 978-0817989026.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 Dreyer, Ronald (1994). Namibia and Southern Africa: Regional Dynamics of Decolonization, 1945-90. London: Kegan Paul International. pp. 73–87, 100–116, 192. ISBN 978-0710304711.

- ↑ Shultz, Richard (1988). Soviet Union and Revolutionary Warfare: Principles, Practices, and Regional Comparisons. Stanford, California: Hoover Institution Press. pp. 121–123, 140–145. ISBN 978-0817987114.

- ↑ Sechaba, Tsepo; Ellis, Stephen (1992). Comrades Against Apartheid: The ANC & the South African Communist Party in Exile. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 184–187. ISBN 978-0253210623.

- ↑ James III, W. Martin (2011) [1992]. A Political History of the Civil War in Angola: 1974-1990. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers. pp. 207–214, 239–245. ISBN 978-1-4128-1506-2.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 Sitkowski, Andrzej (2006). UN peacekeeping: myth and reality. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 80–86. ISBN 978-0-275-99214-9.

- ↑ Clairborne, John (7 Epulelo 1989). "SWAPO Incursion into Namibia Seen as Major Blunder by Nujoma". The Washington Post. Washington DC. Retrieved 18 Febuluwale 2018.

- ↑ Colletta, Nat; Kostner, Markus; Wiederhofer, Indo (1996). Case Studies of War-To-Peace Transition: The Demobilization and Reintegration of Ex-Combatants in Ethiopia, Namibia, and Uganda. Washington DC: World Bank. pp. 127–142. ISBN 978-0821336748.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 60.2 "Namibia Rebel Group Wins Vote, But It Falls Short of Full Control". The New York Times. 15 Novembala 1989. Retrieved 20 Juni 2014.

- ↑ Namibia gains Independence – South African History Online

- ↑ Dierks, Klaus. "7. The Period after Namibian Independence". Klausdierks.com. Retrieved 21 Ogasiti 2020.

- ↑ "Treaty between the Government of the Republic of South Africa and the Government of the Republic of Namibia with respect to Walvis Bay and the off-shore Islands, 28 February 1994" (PDF). United Nations.

- ↑ "Country report: Spotlight on Namibia". Commonwealth Secretariat. 25 Meyi 2010. Archived from the original on 5 Julayi 2010.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 "IRIN country profile Namibia". IRIN. Malichi 2007. Archived from the original on 17 Febuluwale 2010. Retrieved 12 Julayi 2010.

- ↑ "Namibian presidential election won by Swapo's Hage Geingob". BBC News. Disembala 2014.

- ↑ "Namibia's President Hage Geingob wins re-election". BBC News. Disembala 2019.

- ↑ "Rank Order – Area". CIA World Fact Book. Archived from the original on 9 Febuluwale 2014. Retrieved 12 Epulelo 2008.

- ↑ Brandt, Edgar (21 Sekutembala 2012). "Land degradation causes poverty". New Era.

- ↑ "Landsat.usgs.gov". Landsat.usgs.gov. Archived from the original on 7 Sekutembala 2008. Retrieved 26 Juni 2010.

- ↑ Spriggs, A. (2001) Template:WWF ecoregion

- ↑ Cowling, S. 2001. Template:WWF ecoregion

- ↑ Van Jaarsveld, E. J. 1987. The succulent riches of South Africa and Namibia. Aloc, 24: 45–92

- ↑ Smith et al 1993

- ↑ Spriggs, A. (2001) Template:WWF ecoregion

- ↑ "NASA – Namibia's Coastal Desert". nasa.gov. Retrieved 9 Okutobala 2009.

- ↑ "An Introduction to Namibia". geographia.com. Retrieved 9 Okutobala 2009.

- ↑ "NACOMA – Namibian Coast Conservation and Management Project". nacoma.org.na. Archived from the original on 21 Julayi 2009. Retrieved 9 Okutobala 2009.

- ↑ Sparks, Donald L. (1984). "Namibia's Coastal and Marine Development Potential". African Affairs. 83 (333): 477. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a097645.

- ↑ "Paper and digital Climate Section". Namibia Meteorological Services

- ↑ "The Rainy Season". Real Namibia. Archived from the original on 6 Sekutembala 2010. Retrieved 28 Julayi 2010.

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 82.2 "Namibia". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 28 Julayi 2010.

- ↑ Olszewski, John (13 Meyi 2009). "Climate change forces us to recognise new normals". Namibia Economist. Archived from the original on 13 Meyi 2011.

- ↑ AfricaNews (6 Meyi 2019). "Namibia declares national state of emergency over drought". Africanews (in English). Retrieved 20 Meyi 2019.

- ↑ Namibian, The. "State of drought emergency extended". The Namibian (in English). Archived from the original on 10 Malichi 2021. Retrieved 24 Novembala 2020.