ChiCheŵa

ChiCheŵa (panjiso kuti Chinyanja) chiyowoyero cha Bantu icho chikuyowoyeka mu Malaŵi na chiyowoyero cha ŵanthu ŵachoko waka mu Zambia na Mozambique. Chilembo chakwamba chi- chikugwiliskirika ntchito pa viyowoyero, ntheura chiyowoyero ichi chikuchemeka Chichewa na Chinyanja. Mu 1968, pulezidenti Hastings Kamuzu Banda (uyo nayo wakaŵa wa mtundu wa Chewa) wakakhumbanga kuti mu Malaŵi, zina la Chichewa lisinthe kufuma ku Chinyanja.[4] Mu Zambia, chiyowoyero ichi chikuchemeka Nyanja panji Cinyanja/Chinyanja'((chilankhulo) cha nyanja' (kuyowoya za Nyanja ya Malawi).[5]

| ChiCheŵa | |

|---|---|

| Chinyanja | |

| Chichewa, Chinyanja | |

| Native to | Malawi |

| Region | Southeast Africa |

| Ethnicity | Chewa |

Native speakers | 2 million (2020[1])[2] |

| Latin (Chewa alphabet) Mwangwego Chewa Braille | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | ny |

| ISO 639-2 | nya |

| ISO 639-3 | nya |

| Glottolog | nyan1308 |

N.30 (N.31, N.121)[3] | |

| Linguasphere | 99-AUS-xaa – xag |

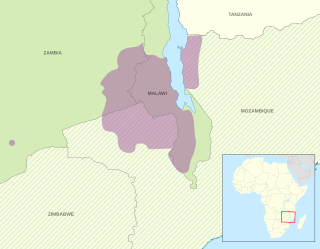

Vigaŵa ivyo chiyowoyero cha Chichewa ndicho chikayowoyeka chomene. Chizungu chikulongora kuti chiyowoyero cha Chichewa ndicho ntchilankhulo cha boma. | |

| Person | Mchewa |

|---|---|

| People | Achewa |

| Language | Chichewa |

Chichewa chili mu gulu limoza la viyowoyero (Guthrie Zone N) na chiTumbuka, Sena na Nsenga.

Kwamba kale, ŵanthu ŵa mu Malawi ŵakuyowoya viyowoyero vya Chichewa na ChiTumbuka. Ndipouli, ciyowoyero ca Tumbuka cikasuzgika comene mu nyengo ya muwuso wa Pulezidenti Hastings Kamuzu Banda, cifukwa mu 1968 cifukwa ca fundo yake yakuti paŵe mtundu umoza na ciyowoyero cimoza, ciyowoyero ici cikaleka kuŵa ca boma mu Malawi. Ntheura, chiyowoyero cha Tumbuka chikafumiskika mu masukulu, pa wayilesi, na mu manyuzipepara.[6] Mu 1994, apo boma la Tumbuka likamba kulamulira na vipani vinandi, ŵakambaso kutegherezga maungano gha pa wayilesi, kweni mabuku na mabuku ghanyake ghakaŵa ghachoko.[7]

Makhalilo

lembaChichewa ndicho chikuyowoyeka chomene mu Malaŵi. Kweniso likuyowoyeka mu chigaŵa cha kumafumiro gha dazi kwa Zambia, kweniso ku Mozambique, chomenechomene mu vigaŵa vya Tete na Niassa. Chikaŵa chiyowoyero chimoza mwa viyowoyero 55 ivyo vikaŵa mu ndege ya Voyager.[8]

Mbiri

lembaŴanthu ŵa mtundu wa Chewa ŵakaŵa ŵa fuko la Maravi, awo ŵakakhalanga ku chigaŵa cha kumafumiro gha dazi kwa Zambia na kumpoto kwa Mozambique m'paka kumwera kwa Mlonga wa Zambezi kwambira m'ma 1500 panji kumasinda.

Zina lakuti "Chewa" (mu chiyowoyero cha Chévas) likalembeka kakwamba na António Gamitto, uyo mu 1831, apo wakaŵa na vyaka 26, wakasankhika kuŵa wachiŵiri kwa mulara wa gulu la ŵanthu awo ŵakaluta ku nkhondo kufuma ku Tete kuluta ku nyumba ya themba Kazembe ku Zambia. Wakenda mu caru ca Themba Undi kumanjiliro gha dazi kwa mapiri gha Dzalanyama, kujumpha mu malo agho sono ni Malawi na kunjira mu Zambia. Pamanyuma, wakalemba nkhani yinyake iyo yikaŵa na nkhani za ŵanthu na viyowoyero. Gamitto wakati ŵanthu ŵa ku Malawi panji Maravi (Maraves) ŵakaŵa ŵanthu awo ŵakalongozgekanga na Themba Undi kumwera kwa mlonga wa Chambwe (pafupi na mphaka ya pakati pa Mozambique na Zambia).

Mulendo munyake wa ku Germany zina lake Sigismund Koelle, uyo wakacitanga mulimo wake mu Sierra Leone, ku West Africa, wakafumba ŵanthu 160 awo ŵakaŵa ŵazga ndipo wakalemba mazgu gha mu viyowoyero vyawo. Mu 1854, wakalemba buku la Polyglotta Africana. Pakati pa ŵazga ŵanyake pakaŵa Mateke, uyo wakayowoyanga chiyowoyero icho wakuchichema kuti "Maravi". Chiyowoyero cha Mateke ntchiyowoyero chakwambilira cha Chiyanja, kweni chikuyowoyeka kumwera. Mwaciyerezgero, mazgu ghakuti zaka ziwiri "vyaka viŵiri" ghakaŵa dzaka dziŵiri mu kayowoyero ka Mateke, apo kwa Salimini, uyo wakaŵa muphaci wa Johannes Rebmann, uyo wakafuma ku Lilongwe, ghakaŵa bzaka bziŵiri. Mazuŵa ghano napo mazgu agha ghakusangika mu chiyowoyero chinyake.

Padera pa mazgu ghachoko waka agho ghakalembeka na Gamitto na Koelle, mazgu ghakwambilira gha Chichewa ghakalembeka na Johannes Rebmann mu buku lake la Dictionary of the Kiniassa Language, ilo likalembeka mu 1853. Rebmann wakaŵa mishonale ndipo wakakhalanga kufupi na Mombasa, mu caru ca Kenya. Wakasanga fundo iyi kwa muzga wa ku Malawi, uyo wakamanyikwanga na zina la Ciswahili lakuti Salimini. Salimini, uyo wakafuma ku Mphande, mu chigaŵa cha Lilongwe, nayo wakawona mphambano pakati pa chiyowoyero chake, icho wakachichemanga Kikamtunda, "chiyowoyero cha ku mapiri", na chiyowoyero cha Kimaravi icho ŵanthu ŵakayowoyanga kumwera.[9]

Buku lakwamba lakuti A Grammar of the Chinyanja language as spoken at Lake Nyasa, ilo lili na mazgu gha Chingelezi na Chingelezi, likalembeka na Alexander Riddel mu 1880. Mu viyowoyero vinyake vyakwambilira muli mazgu gha Chichinyanja agho George Henry (1891) na M.E. Woodward's A vocabulary of English?? Chinyanja and Chinyanja?? English: as spoken at Likoma, Lake Nyasa (1895). William Percival Johnson ndiyo wakang'anamura Baibolo lose mu chiyowoyero cha Nyanja cha pa Likoma Island, ndipo wakalilemba mu 1912. Baibolo linyake la Buku Lopatulika ndilo Mau a Mulungu likalembeka mu chiyowoyero cha ku Central Region cha m'ma 1900-1922 na ŵamishonale ŵa Dutch Reformed Mission na Church of Scotland. Mu 2016, buku ili likang'anamulika na kunozgaso.

Chiyowoyero chinyake chakwambilira icho ŵanthu ŵakayowoyanga chikaŵa chiyowoyero cha Kasungu. Buku ili ndilo likaŵa lakwamba kulembeka na munthu wa ku America, ndipo likalembeka pamoza na Hastings Kamuzu Banda, uyo wakaŵa mulongozgi wakwamba wa charu cha Malawi. Ciyowoyero ici nchakuzirwa comene cifukwa ndico cikaŵa cakwamba kulongora umo mazgu ghakupambanirana. Mabuku gha mazuŵa ghano ghakulongosora umo chichewa chikugwilira ntchito nga ni Mtenje (1986), Kanerva (1990), Mchombo (2004) na Downing & Mtenje (2017).

Mu vyaka vyasonosono apa, chiyowoyero ichi chasintha chomene, ndipo chiyowoyero cha Chichewa icho ŵanthu ŵakuyowoya mu mizi na chiyowoyero cha ŵanthu awo ŵakukhala mu matawuni vikupambana.[10]

Kuyowoya mazgu

lembaMa vawelo

lembaChichewa chili na mazgu ghankhondi: a, ɛ, i, ɔ, u. Nyengo zinyake tikuwona mavowel ghatali panji ghaŵiri, nga ni áákúlu 'likuru' (class 2), kufúula 'kuchemerezga.' Para lizgu lafika kuumaliro wa sentesi, lizgu lakwamba lakwamba likuŵa litali, kupaturako mazina na mazgu gha Cchewa yayi, nga ni Muthárika panji ófesi, apo lizgu lakwamba lakwamba likuŵa lifupi. Mazgu ghakuti "u" panji "i" agho ghazunulika mu mazgu nga ni láputopu 'laptop' panji íntaneti 'internet' ghakuŵa ghambura kuzunulika.[11]

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | u | |

| Open-mid | ɛ | ɔ | |

| Open | a |

Consonants

lembaVilembo vya Chewa vingaŵa vyakupambanapambana (pakuti vikwendera pamanyuma pa vowel), labialised (pakuti vikwendera pamanyuma pa w), panji palatalised (pakuti vikwendera pamanyuma pa y):

- ba, kha, ga, fa, ma, sa etc.

- bwa, khwa, gwa, fwa, mwa, swa etc.

- bza, tcha, ja, fya, nya, sha etc.

Mu chiyowoyero ichi, pa malo gha bya pakaŵa bza, pa malo gha gya pakaŵa ja, ndipo pa sya pakaŵa sha.

Nthowa yinyake iyo tikuyowoyera mazgu agha njakuti:

- ba, da, ga

- pa, ta, ka

- pha, tha, kha

- ma, na, ng'a

- wa, la, ya

Para munthu wakuyowoya mazgu ghakupambanapambana, mazgu agha ghakung'anamulika kuti [f] na [s].

- mba, ngwa, nja, mva, nza etc.

- mpha, nkhwa, ntcha, mfa, nsa etc.

Ntheura, mazgu agho ghangaŵa pa tabuleti ghangaŵa nga ni agha:

| Labial | Dental | Velar/Palatal | Glottal | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | palatalised | labialised | plain | palatalised | labialised | plain | labialised | |||

| Nasal | ma /m/ |

mya /mʲ/ |

mwa /mʷ/ |

na /n/ |

nya /nʲ/ |

ng'a /ŋ/ |

ng'wa /ŋʷ/ |

|||

| Stop | voiceless | pa /p/ |

pya /pʲ/ |

pwa /pʷ/ |

ta /t/ |

tya /tʲ/ |

twa /tʷ/ |

ka /k/ |

kwa /kʷ/ |

|

| aspirated | pha /pʰ/ |

phwa /pʷʰ/ |

tha /tʰ/ |

thya /tʲʰ/ |

thwa /tʷʰ/ |

kha /kʰ/ |

khwa /kʷʰ/ |

|||

| Pre-nasalized aspirated | mpha /ᵐpʰ/ |

mphwa /ᵐpʷʰ/ |

ntha /ⁿtʰ/ |

nthya /ⁿtʲʰ/ |

nthwa /ⁿtʷʰ/ |

nkha /ᵑkʰ/ |

nkhwa /ᵑkʷʰ/ |

|||

| voiced | ba /ɓ/ |

bwa /ɓʷ/ |

da /ɗ/ |

dya /ɗʲ/ |

dwa /ɗʷ/ |

ga /ɡ/ |

gwa /ɡʷ/ |

|||

| Pre-nasalized voiced | mba /ᵐb/ |

mbwa /ᵐbʷ/ |

nda /ⁿd/ |

ndya /ⁿdʲ/ |

ndwa /ⁿdʷ/ |

nga /ᵑɡ/ |

ngwa /ᵑɡʷ/ |

|||

| Affricate | voiceless | psa /pʃʲ/ |

tsa /t͡s/ |

tswa /t͡sʷ/ |

cha /t͡ʃ/ |

|||||

| aspirated | tcha /t͡ʃʰ/ |

|||||||||

| Pre-nasalized aspirated | mpsa /ᵐpsʲ/ |

ntcha /ⁿt͡ʃʰ/ |

||||||||

| voiced | bza /bʒʲ/ |

dza /d͡z/ |

(dzwe) /d͡zʷ/ |

ja /d͡ʒ/ |

||||||

| Pre-nasalized voiced | mbza /ᵐbzʲ/ |

(ndza) /ⁿd͡z/ |

nja /ⁿd͡ʒ/ |

|||||||

| Fricative | voiceless | fa /f/ |

(fya) /fʲ/ |

fwa /fʷ/ |

sa /s/ |

sha /ʃ/ |

swa /sʷ/ |

(ha) /h/ | ||

| Pre-nasalized | mfa /ᶬf/ |

nsa /ⁿs/ |

nswa /ⁿsʷ/ |

|||||||

| voiced | va /v/ |

(vya) /vʲ/ |

vwa /vʷ/ |

za /z/ |

(zya) /zʲ~ʒ/ |

zwa /zʷ/ |

||||

| Pre-nasalized voiced | mva /ᶬv/ |

nza /ⁿz/ |

nzwa /ⁿzʷ/ |

|||||||

| Approximant | (ŵa) /β/ |

wa /w/ |

la/ra /ɽ/ |

lwa/rwa /ɽʷ/ |

ya /j/ |

|||||

Kulemba uko ŵakugwiliskira nchito apa nkhwa mu 1973 ndipo ndiko ŵakugwiliskira nchito comene mu Malaŵi mazuŵa ghano.[12]

Notes on the consonants

- Mu viyowoyero vinandi, mazgu gha Chewa b na d (para ghandang'anamulike) ghakuzunulika mwakubisika. Kweni pali mazgu gha b na d, agho ghakusangika chomene mu mazgu gha ku vyaru vinyake, nga ni bála 'bar', yôdúla 'expensive' (kufuma ku Afrikaans duur) (mwakupambana na mazgu gha b na d agho ghakusangika mu mazgu gha ku vyaru vinyake nga ni bála 'wound' na yôdúla 'which cuts'). Lizgu lakuti d likusangikaso mu kudínda 'kusindamira (chikalata)'na mdidi 'kukhwima mtima.'

- Kale ŵanthu ŵakatemwanga kupulika mazgu ghakuti bv na pf, kweni sono ghakusinthika na v na f. Mu dikishonare la Mtanthauziramawu wa Chinyanja ilo likapangika na Yunivesite ya Malawi, mazgu ghakuti bv na pf ghakusangikamo yayi, kweni ghaŵiri panji ghatatu.

- Atkins wakulongosora kuti mzere wa bz ni "muvi wa alveolar-labilized fricative". Mazgu agha ghakuyana waka na [bʒ] panji [bʒj]. Mwakuyana waka, lizgu lakuti ps likuyowoyeka nga ni [pʃ] panji [pʃj].

- Mazgu agho ghakulembeka ch, k, p, na t ghakuyowoyeka mwakupepuka kuluska gha Cingelezi. Stevick wakalongosora kuti para munthu wakuyowoya mwakufwatuka, mazgu ghatatu ghakwamba ghakusinthika na mazgu ghakuti [ʒ], [ɣ] na [β]. Mu chigaŵa cha -ti (nga ni angáti? "Vinga"), t yingapupulika.

- h is also used in Chewa but mostly only in loanwords such as hotéra 'hotel', hátchi 'horse', mswahála 'monthly allowance given to chiefs'.

- j is described by Scotton and Orr as being pronounced "somewhat more forward in the mouth" than in English and as sounding "somewhere between an English d and j".[13]

- l and r are the same phoneme,[14] representing a retroflex tap [ɽ], approximately between [l] and [r]. According to the official spelling rules, the sound is written as 'r' after 'i' or 'e', otherwise 'l'. It is also written with 'l' after a prefix containing 'i', as in lilíme 'tongue'.[15][16]

- m ni syllabic [m̩] mu mazgu agho ghali kufuma ku mu, e.g. m'balé'mubwezi' (3 syllable), mphunzitsi'musambizgi' (4 syllable), anáḿpatsa 'wakamupa' (5 syllable). Ndipouli, mu mazgu gha kilasi 9, nga mphátso 'chawanangwa,' mbale 'chiŵiya,' panji mfíti'muthemba,' kweniso mu mazgu gha kilasi 1, mphaká'mphaka,' m wakuzunulika mwakudumura ndipo wakuŵa kuti ni syllable yayi. Mu viyowoyelo vya ku Southern Region mu Malaŵi, syllabic m mu mazgu nga mkángo 'nkhalamu' yikuyowoyeka mwakuyana waka, i.e. [ŋ̍.ká.ŋɡo] (na vilembo vitatu), kweni mu Central Region, yikuyowoyeka nga umo yikulembeka, i.e. [m̩.ká.ŋɡo].[17]

- n, mu umoza nga nj, ntch, nkh etc., wakuyana na lizgu lakunjilira lakulondezgapo ili, ndiko kuti, likuzunulika [ɲ] panji [ŋ] mwakuyana na umo viliri. Mu mazgu gha kilasi 9, nga njóka 'njoka' panji nduná'mupharazgi' lizgu ili likuyowoyeka mwakudumura chomene, nga ni chigaŵa cha syllable yakulondezgapo. Ndipouli, [n] nayo wangaŵa wa syllabic, para wafuma mu ndi 'ndi' panji ndí 'ndipo', nga ni ń'kúpíta 'ndipo kwenda'; kweniso mu nyengo iyo yajumpha, nga ni ankápítá 'wakendanga.' Mu mazgu ghanyake nga ni bánki panji íntaneti, mazgu agha ghakusangika mu viyowoyero vinyake.

- ng wakuzunulika [ŋɡ] nga ni'munwe' ndipo ng?? wakuzunulika [ŋ] nga ni 'wakwimba.' Vilembo viŵiri ivi vingaŵa pakwamba pa lizgu: ngoma 'kudu', ng'ombe 'ng'ombe panji ng'ombe.'

- w mu vimanyikwiro vya awu, ewu, iwu, owa, uwa (mwachitsanzo mawú'mawu', msewu'msewu', liwú 'kulira', lowa 'kunjira', duwa'maluŵa') nangauli kanandi yikulembeka kweni kanandi yikuyowoyeka yayi. Vinthu vyakupambanapambana nga ni gwo panji mwo vikusangika yayi; ntheura ngwábwino (cipepara ca ndi wábwino) 'ndi muwemi' kweni ngóípa (cipepara ca ndi wóípa) 'ndi muheni'; mwalá 'libwe' kweni móto'moto.'

- Ŵ, "ŵakuzingilizgika na milomo na lulimi luli pafupi na i", kale ŵakayowoyanga mu viyowoyero vya ku Central Region kweni sono ŵakulizga viŵi yayi. ("Nkhukayika usange ŵanthu ŵanandi awo ŵakuyowoya [β] ŵali na mazgu agha". Chizindikiro chakuti 'ŵ' kanandi chikuŵavya mu mabuku gha mazuŵa ghano nga ni manyuzipepara. Mu viyowoyero vinyake, lizgu ili likuzunulika pambere a, i, na e vindanjire. Ŵanthu ŵanyake awo ŵakumanya malulimi (nga ni (Watkins) vikuyana waka na [β] mu Cisipanishi.[18]

- zy (nga ni mu zyoliká 'kuzgokera pasi nga ni mbunda') lingazunulika [ʒ].[19]

Kapulikikilo

lembaNga umo viliri na viyowoyero vinyake vinandi vya ŵanthu ŵa mtundu wa Bantu, chiyowoyero cha Chichewa nacho chili na mazgu ghakupambanapambana. Mu chiyowoyero ichi, mazgu ghakugwiliskira nchito nthowa zakupambanapambana. Cakwamba, lizgu lililose lili na mazgu ghake.[20]

- munthu [mu.ⁿtʰu] 'person' (Low, Low)

- galú [ɡă.ɽú] 'dog' (Rising, High)

- mbúzi [ᵐbû.zi] 'goat' (Falling, Low)

- chímanga [t͡ʃí.ma.ᵑɡa] 'maize' (High, Low, Low)

Kanandi lizgu likuŵa na lizgu limoza pera la mazgu ghapachanya (kanandi pa lizgu limoza pa mazina ghatatu ghaumaliro), panji palije lizgu nanga ndimoza. Ndipouli, mazgu ghakupambanapambana ghangaŵa na mazgu ghakupambanapambana, nga ni:

- chákúdyá [t͡ʃá.kú.ɗʲá] 'food' (High, High, High; derived from chá + kudyá, 'a thing of eating')

Cinthu caciŵiri cakuzirwa ico mazgu agha ghakung'anamura ni lizgu lakuyowoya. Nyengo yiliyose ya lizgu ili yili na mazgu ghake. Mwaciyelezgero, lizgu lakuti sono (present habitual) lili na mazgu ghapachanya pa lizgu lakwamba na laumaliro, apo lizgu linyake lili na mazgu ghachoko.

- ndí-ma-thandíza 'I (usually) help'

- ndí-ma-píta 'I (usually) go'

Kweni mazgu ghakuti recent past continuous na present continuous, ghakuŵa na mazgu gha pa syllable yacitatu:

- ndi-ma-thándiza 'I was helping'

- ndi-ma-píta 'I was going'

- ndi-ku-thándiza 'I am helping'

- ndi-ku-píta 'I am going'

Kweniso mazgu ghangavumbura usange lizgu likugwira ntchito mu chigaŵa chikuru panji mu chigaŵa chakulondezgapo.[21][22]

- sabatá yatha 'the week has ended'

- sabatá yátha 'the week which has ended (i.e. last week)'

Cinthu cacitatu ico ŵanthu ŵakucita na mazgu gha Chewa nkhusambizga mazgu. Mwaciyelezgero, para mazgu ghafuma pakati pa sentesi, mazgu gha uyo wakuyowoya ghakukwera. Nyengo zinyake tikupulika mazgu ghanyake, nga ni mazgu agho ghakwera panji kukhira paumaliro wa fumbo lakuti enya panji yayi.[23][24]

Kalembelo

lembaMa kilasi gha Mazina

lembaVizunuli vya Chichewa vili kugaŵika mu vigaŵa vinandi, ndipo ŵanthu ŵa ku Malawi ŵakuvizunura kuti "Mu-A-", kweni ŵanthu ŵa ku Bantu ŵakuvizunura kuti "1/2". Kanandi mazgu agha ghakupangika mu vigaŵa viŵiri. Ndipouli, mazgu ghakupambanapambana nagho ghangaŵapo, comenecomene na mazgu agho ŵali kuwombora. Mwaciyelezgero, lizgu lakuti bánki 'banki,' ilo likung'anamura mazgu ghakupambanapambana gha kilasi 9, lili na mabánki (kalasi 6).

Para tikupeleka mazina ku chigaŵa chinyake, pakwamba tikugwiliskira ntchito chigaŵa chakwamba. Para palije lizgu lakwamba, panji para lizgu lakwamba ndakubudika, mazgu agho ghali mu lizgu lakwamba (onani pasi apa) ghakovwira kuti munthu wamanye zina la lizgu. Mwaciyelezgero, mazgu ghakuti katúndu 'vinthu' ghali mu gulu la 1, cifukwa ghali na lizgu lakuti uyu 'ici.'

Zina mwa mazina agha ghali mu gulu limoza pera, nga ni tomáto 'tomato(es)'(class 1), mowa 'beer' (class 3), malayá'shirt(s)'(class 6), udzudzú'mosquito(es)'(class 14), ndipo ghakusintha yayi pakati pa umoza na unandi. Nangauli vili nthena, kweni mazgu agha ghangaŵapo: tomáto muwíri 'thomato ziŵiri', mowa uwíri 'biyere ziŵiri', malayá amódzi'shati limoza', udzudzú umódzi 'nyerere yimoza.'

Chigaŵa cha 11 (Lu-) chilipo yayi mu Chichewa. Mazgu nga ni lumo 'nkhwazi' na lusó 'nkhongono' ghakuwoneka kuti ghali mu gulu la 5/6 (Li-Ma-) ndipo ghakukolerana na gulu ili.[25]

- Mu-A- (1/2): munthu pl. anthu 'person'; mphunzitsi pl. aphunzitsi 'teacher'; mwaná pl. aná 'child'

(1a/2): galú pl. agalú 'dog'. Class 1a refers to nouns which have no m- prefix.

The plural a- is used only for humans and animals. It can also be used for respect, e.g. aphunzitsi áthu 'our teacher'

(1a/6): kíyi pl. makíyi 'key'; gúle pl. magúle 'dance'

(1a): tomáto 'tomato(es)'; katúndu 'luggage, furniture'; feteréza 'fertilizer' (no pl.) - Mu-Mi- (3/4): mudzi pl. midzi 'village'; mténgo pl. miténgo 'tree'; moyo pl. miyoyo 'life'; msika pl. misika 'village'

(3): mowa 'beer'; móto 'fire'; bowa 'mushroom(s)' (no pl.) - Li-Ma- (5/6): dzína pl. maína 'name'; vúto pl. mavúto 'problem'; khásu pl. makásu 'hoe'; díso pl. masó 'eye'

Often the first consonant is softened or omitted in the plural in this class.

(6): madzí 'water', mankhwála 'medicine', maló 'place' (no sg.) - Chi-Zi- (7/8): chinthu pl. zinthu 'thing'; chaká pl. zaká 'year'

(7): chímanga 'maize'; chikóndi 'love' (no pl.) - I-Zi- (9/10): nyumbá pl. nyumbá 'house'; mbúzi pl. mbúzi 'goat'

(10): ndevu 'beard'; ndíwo 'relish'; nzerú 'intelligence' (no sg.)

(9/6): bánki pl. mabánki 'bank' - Ka-Ti- (12/13): kamwaná pl. tianá 'baby'; kanthu pl. tinthu 'small thing'

(12): kasamalidwe 'method of taking care'; kavinidwe 'way of dancing' (no pl.)

(13): tuló 'sleep' (no sg.) - U-Ma- (14): usíku 'night time'; ulimi 'farming'; udzudzú 'mosquito(es)' (no pl.)

(14/6): utá pl. mautá 'bow'

Infinitive class:

- Ku- (15): kuóna 'to see, seeing'

Locative classes:

- Pa- (16): pakamwa 'mouth'

- Ku- (17): kukhosi 'neck'

- Mu- (18): mkamwa 'inside the mouth'

Concords

lembaVizunuli, vimanyikwiro, na viyowoyero vinyake vikwenera kukolerana na mazina gha Chichewa. Ivi vikucitika na vilembo vyakwambilira, nga ni:

- Uyu ndi mwaná wángá 'this is my child' (class 1)

- Awa ndi aná ángá 'these are my children' (class 2)

- Ichi ndi chímanga chánga 'this is my maize' (class 7)

- Iyi ndi nyumbá yángá 'this is my house' (class 9)

Nyengo zinandi pakuyowoya za ŵalara, ŵakuyowoya za gulu laciŵiri. Kuyana na Corbett na Mtenje, lizgu lakuti bambo 'baba,' nangauli ndakuyana waka na lizgu linyake, kweni likuyana waka na lizgu linyake.[26]

Vilembo vyakupambanapambana ivi vili pa tabuleti iyi:

| noun | English | this | that | pron | subj | object | num | rem | of | of+vb | other | adj | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | mwaná | child | uyu | uyo | yé- | a- | mú/ḿ- | m/(mu)- | uja | wá | wó- | wína | wám- |

| 2 | aná | children | awa | awo | ó- | a- | -á/wá- | a- | aja | á | ó- | éna | áa- |

| 3 | mutú | head | uwu | uwo | wó- | u- | -ú- | u- | uja | wá | wó- | wína | wau- |

| 4 | mitú | heads | iyi | iyo | yó- | i- | -í/yí- | i- | ija | yá | yó- | ína | yái- |

| 5 | díso | eye | ili | ilo | ló- | li- | -lí- | li- | lija | lá | ló- | lína | láli- |

| 6 | masó | eyes | awa | awo | ó- | a- | -wá- | a- | aja | á | ó- | éna | áa- |

| 7 | chaká | year | ichi | icho | chó- | chi- | -chí- | chi- | chija | chá | chó- | chína | cháchi- |

| 8 | zaká | years | izi | izo | zó- | zi- | -zí- | zi- | zija | zá | zó- | zína | zázi- |

| 9 | nyumbá | house | iyi | iyo | yó- | i- | -í/yí- | i- | ija | yá | yó- | ína | yái- |

| 10 | nyumbá | houses | izi | izo | zó- | zi- | -zí- | zi- | zija | zá | zó- | zína | zázi- |

| 12 | kamwaná | baby | aka | ako | kó- | ka- | -ká- | ka- | kaja | ká | kó- | kéna | káka- |

| 13 | tianá | babies | iti | ito | tó- | ti- | -tí- | ti- | tija | tá | tó- | tína | táti- |

| 14 | utá | bow | uwu | uwo | wó- | u- | -ú- | u- | uja | wá | wó- | wína | wáu- |

| 15 | kugúla | buying | uku | uko | kó- | ku- | -kú- | ku- | kuja | kwá | kó- | kwína | kwáku- |

| 16 | pansí | underneath | apa | apo | pó- | pa- | -po | pa- | paja | pá | pó- | péna | pápa- |

| 17 | kutsogoló | in front | uku | uko | kó- | ku- | -ko | ku- | kuja | kwá | kó- | kwína | kwáku- |

| 18 | mkatí | inside | umu | umo | mó- | m/mu- | -mo | m/mu- | muja | mwá | mó- | mwína | mwám'- |

Pali mazina 17 ghakupambanapambana, kweni pakuti ghanyake ghali na mazina ghakupambanapambana, pali mazina 12 pera.

Examples of the use of concords

lembaMu viyelezgero ivyo vili pasi apa, mazgu gha viyowoyero ivi ghakulongosoreka na mazina gha viyowoyero vya mu kilasi 1 na 2.

Demonstratives 'this' and 'that'

lemba- uyu ndaní? 'who is this?'; awa ndaní? 'who are these?' (or: 'who is this gentleman?' (respectful))

- mwaná uyu (mwanáyu) 'this child'; aná awa (anáwa) 'these children'

- mwaná uyo (mwanáyo) 'that child'; aná awo (anáwo) 'those children'

Kanandi ŵanthu ŵakugwiliskira ntchito vilembo ivi.

Pronominal yé, (w)ó etc.

lembaPara mazgu agha ghalembeka pambere mazgu ghanyake ghandalembeke, panji para ghalembeka pambere mazgu ghanyake ghandambe kulembeka, ghakuŵa nga ni mazgu ghakuti "iyo" na "iwo".

- iyé 'he/she'; iwó 'they' (or 'he/she' (respectful))

- náye 'with him/her'; náwo 'with them' (or 'with him/her' (respectful))

- ndiyé 'it is he/she'; ndiwó 'it is they'

Pa visambizgo vinyake padera pa visambizgo 1 na 2, mazgu ghakulongosora ghakugwiliskirika nchito m'malo mwa zina la munthu, nga ni ichi panji icho. Kweni pali viyowoyero vinyake ivyo vili na lizgu lakuti ná- na ndi- nga ni nácho na ndichó.

yénse, yékha, yémwe

lembaViyelezgelo vitatu vya zina lakuti yénse 'wose', yékha 'yekha', yémwe 'iyo mweneyuyo' (panji 'uyo') vili na viyelezgelo vyakuyana waka vyakuti yé- na (w) ó-, pa nyengo iyi ni viyelezgelo:

- Maláwi yénse 'the whole of Malawi'

- aná ónse 'all the children'

- yékha 'on his/her own'

- ókha 'on their own'

- mwaná yemwéyo 'that same child'

- aná omwéwo 'those same children'

Mu magulu ghaŵiri na ghankhondi na limoza, ó- kanandi yikuzgoka wó- (nga ni wónse kwa ónse na vinyake).

Lizgu lakuti álíyensé 'wose' lili kufuma ku lizgu lakuti áli 'uyo waliko' na lakuti yénse 'wose.' Vigaŵa vyose viŵiri vya lizgu ili vili na mazgu ghakuyana:

- mwaná álíyensé 'every child'

- aná awíri álíonsé 'every two children'

- nyumbá ílíyonsé 'every house' (class 4)

- chaká chílíchonsé 'every year' (class 7)

Subject prefix

lembaNga umo vikuŵira na viyowoyero vinyake vya ŵanthu ŵa ku Bantu, viyowoyero vyose vya Chichewa vili na mazgu ghakwamba agho ghakukolerana na chiŵaro cha chiŵaro. Mu Chichewa cha mazuŵa ghano, chiŵiya chakwamba cha chiŵiya 2 (kale ŵa-) chazgoka a-, icho chikuyana waka na chiŵiya chakwamba cha chiŵiya 1:

- mwaná ápita 'the child will go'; aná ápita 'the children will go'

Nyengo yakufikapo (wapita 'wakaluta', apita 'ŵaluta') yili na vigaŵa vyakupambana na nyengo zinyake (wonani pasi apa).

améne 'who'

lembaLizgu lakuti améne 'uyo' na lizgu lakuti demonstrative améneyo ghakugwiliskira ntchito mazgu ghakuyana waka nga ni verebu:

- mwaná améne 'the child who'

- aná améne 'the children who'

- mwaná améneyo 'that child'

- aná aménewo 'those children'

- nyumbá iméneyo 'that house'

- nyumbá ziménezo 'those houses'

Object prefix

lembaMu Chichewa, ntchakukhumbikwa yayi kugwiliskira ntchito chigaŵa chakwamba. Para lizgu ili lalembeka, likuŵa panthazi pa lizgu la chiyowoyero, ndipo likuyana na lizgu ilo likuyowoyeka:

- ndamúona 'I have seen him/her'; ndawáona 'I have seen them' (sometimes shortened to ndaáona).

The object prefix of classes 16, 17, and 18 is usually replaced by a suffix: ndaonámo 'I have seen inside it'.

The same prefix with verbs with the applicative suffix -ira represents the indirect object, e.g. ndamúlembera 'I have written to him'.

Numeral concords

lembaNumeral concords are used with numbers -módzi 'one', -wíri 'two', -tátu 'three', -náyi 'four', -sanu 'five', and the words -ngáti? 'how many', -ngápo 'several':

- mwaná mmódzi 'one child'; aná awíri 'two children'; aná angáti? 'how many children?'

Chiŵiya chakwamba m- chikuzgoka mu- pambere -wiri: tomáto muwíri'matamati ghaŵiri.'

Nambara ya khúmi 'kumi' yikukolerana yayi.

Demonstratives uja and uno

lembaViyezgo vya kujilongora vya uja 'uyo mukumumanya' na uno 'uyo tili mu' vikuyana waka na viyezgo vya u- na a- mu kilasi 1 na 2. Pa vifukwa vinyake, cigaŵa ca 1 uno nchacilendo:

- mwaná uja 'that child (the one you know)'; aná aja 'those children' (those ones you know)

- mwezí uno 'this month (we are in)' (class 3); masíkú ano 'these days'; ku Maláwí kuno 'here in Malawi (where we are now)' (class 17).

Perfect tense subject prefix

lembaMazgu gheneagha w- (ghakufuma ku u-) na a-, pamoza na vowel a, ghakupangiska kuti chiŵiya icho chikwimira chiŵiya chinyake chiŵe mu nyengo yakufikapo. Mu lizgu la unandi, vilembo viŵiri ivi vikusazgikana na kuzgoka lizgu limoza:

- mwaná wapita 'the child has gone; aná apita 'the children have gone'

Possessive concord

lembaThe concords w- (derived from u-) and a- are also found in the word á 'of':

- mwaná wá Mphátso 'Mphatso's child'; aná á Mphátso 'Mphatso's children'

The same concords are used in possessive adjectives -ánga 'my', -áko 'your', -áke 'his/her/its/their', -áthu 'our', -ánu 'your (plural or respectful singular), -áwo 'their'/'his/her' (respectful):

- mwaná wángá 'my child'; aná ángá 'my children'

-áwo 'their' is used only of people (-áke is used for things).

Wá 'of' can be combined with nouns or adverbs to make adjectives:

- mwaná wánzérú 'an intelligent child'; aná ánzérú 'intelligent children'

- mwaná ábwino a good child'; aná ábwino 'good children'

In the same way wá 'of' combines with the ku- of the infinitive to make verbal adjectives. Wá + ku- usually shortens to wó-, except where the verb root is monosyllabic:

- mwaná wókóngola 'a beautiful child'; aná ókóngola 'beautiful children'

- mwaná wákúbá 'a thieving child'; aná ákúbá 'thieving children'

-ína 'other' and -ení-éní 'real'

lembaThe same w- and a- concords are found with the words -ína 'other' and -ení-éní 'real'. In combination with these words the plural concord a- is converted to e-:

- mwaná wína 'a certain child, another child'; aná éna 'certain children, other children'

- mwaná weníwéní 'a real child'; aná eníéní 'real children'

Double-prefix adjectives

lembaCertain adjectives (-kúlu 'big', -ng'óno 'small'; -(a)múna 'male', -kázi 'female'; -táli 'long', 'tall', -fúpi 'short'; -wisi 'fresh') have a double prefix, combining the possessive concord (wá-) and the number concord (m- or mw-):

- mwaná wáḿkúlu 'a big child'; aná áákúlu 'big children'

- mwaná wáḿng'óno 'a small child'; aná ááng'óno 'little children'

- mwaná wámwámúna 'a male child'; aná áámúna 'male children'

- mwaná wáḿkázi 'a female child'; aná áákázi 'female children'

Historic changes

lembaEarly dictionaries, such as those of Rebmann, and of Scott and Hetherwick, show that formerly the number of concords was greater. The following changes have taken place:

- Class 2 formerly had the concord ŵa- (e.g. ŵanthu aŵa 'these people'), but this has now become a- for most speakers.

- Class 8, formerly using dzi- (Southern Region) or bzi/bvi/vi- (Central Region) (e.g. bzaká bziŵíri 'two years'),[27] has now adopted the concords of class 10.

- Class 6, formerly with ya- concords (e.g. mazira aya 'these eggs'),[28] now has the concords of class 2.

- Class 11 (lu-) had already been assimilated to class 5 even in the 19th century, although it still exists in some dialects of the neighbouring language Tumbuka.

- Class 14, formerly with bu- concords (e.g. ufá bwángá 'my flour'),[29] now has the same concords as class 3.

- Class 13 (ti-) had tu- in Rebmann's time (e.g. tumpeni utu 'these small knives'). This prefix still survives in words like tuló 'sleep'.

In addition, classes 4 and 9, and classes 15 and 17 have identical concords, so the total number of concord sets (singular and plural) is now twelve.

Ntchito

lembaFormation of tenses

lembaMu Chichewa, mazgu gha nyengo ghakupambana mu nthowa ziŵiri. Nyengo zinyake mazgu ghaŵiri ghakuyana waka ndipo ghakupambana waka na mazgu ghanyake. Mu viyelezgero vyakulondezgapo, chikhwangwani cha nyengo chili pasi:[30][31]

- ndi-ku-gúla 'I am buying'

- ndí-ma-gúla 'I usually buy'

- ndi-ma-gúla 'I was buying', 'I used to buy'

- ndí-dzá-gula 'I will buy (tomorrow or in future)'

- ndí-ká-gula 'I will buy (when I get there)'

One tense has no tense-marker:

- ndí-gula 'I will buy (soon)'

Para munthu wakuyowoya mazgu gha nyengo, wangasazgirako mazgu ghanyake agho ghakumanyikwa na zina lakuti 'aspect-markers.' Ni -má- 'nyengozose, kanandi' -ká- 'kwenda na', -dzá 'kwiza na' panji 'kunthazi,' na -ngo- 'yekha,' 'pamoza pera.' Viŵikilo ivi vingagwiliskikaso nchito pavyekha, nga ni vilembo vya nyengo (yaniskani -ma- na -dza- mu ndondomeko ya nyengo iyo yili pacanya apa). Mwaciyelezgero:

- ndi-ku-má-gúlá 'I am always buying'[32]

- ndi-ná-ká-gula 'I went and bought'[33]

- ndí-má-ngo-gúla 'I just usually buy'[34]

Compound tenses, such as the following, are also found in Chichewa:[35]

- nd-a-khala ndí-kú-gúla 'I have been buying'

Subject-marker

lembaViyezgo vya Chichewa (kupaturako mazgu ghakuchiska na mazgu ghambura kumara) vikwamba na lizgu ilo likuyana na lizgu ilo likuyowoyeka. Ŵanthu ŵanyake awo ŵakumanya maluso gha vilembo ŵakuchema chilembo ichi kuti'subject-marker'.[36]

- (ife) ti-ku-píta 'we are going'

- mténgo w-a-gwa (for *u-a-gwa) 'the tree has fallen'[37]

The subject-marker can be:

- Personal: ndi- 'I', u- 'you (singular)', a- 'he, she', ti- 'we', mu- 'you (plural or polite)', a- 'they'; 'he/she (respectful or polite). (In the perfect tense, the subject-marker for 'he, she' is w-: w-a-pita 'he has gone'.)[38]

- Impersonal: a- (class 1, 2 or 6), u- (class 3 or 14), i- (class 4 or 9), li- (class 5), etc.

- Locative: ku-, pa-, mu-

An example of a locative subject-marker is:

- m'madzí muli nsómba 'in the water there are fish'[39]

Both the 2nd and the 3rd person plural pronouns and subject-markers are used respectfully to refer to a single person:[40]

- mukupíta 'you are going' (plural or respectful)

- apita 'they have gone' or 'he/she has gone' (respectful)

Except in the perfect tense, the 3rd person subject marker when used of people is the same whether singular or plural. So in the present tense the 3rd person subject-marker is a-:

- akupíta 'he/she is going'

- akupíta 'they are going', 'he/she is going' (respectful)

But in the perfect tense wa- (singular) contrasts with a- (plural or respectful):

- wapita 'he/she has gone'

- apita 'they have gone', 'he/she has gone' (respectful)

When the subject is a noun not in class 1, the appropriate class prefix is used even if referring to a person:

- mfúmu ikupíta 'the chief is going' (class 9)

- tianá tikupíta 'the babies are going' (class 13)

Object-marker

lembaAn object-marker can also optionally be added to the verb; if one is added it goes immediately before the verb-stem.[41] The 2nd person plural adds -ni after the verb:

- ndí-ma-ku-kónda 'I love you' (ndi = 'I', ku = 'you')

- ndí-ma-ku-kónda-ni 'I love you' (plural or formal)

The object-marker can be:

- Personal: -ndi- 'me', -ku- 'you', -mu- or -m'- 'him, her', -ti- 'us', -wa- or -a- 'them', 'him/her (polite)'.

- Impersonal: -mu- (class 1), -wa- (class 2), -u- (class 3 or 14), etc.

- Locative: e.g. m'nyumbá mu-ku-mú-dzíwa 'you know the inside of the house';[42] but usually a locative suffix is used instead: nd-a-oná-mo 'I have seen inside it'

- Reflexive: -dzi- 'himself', 'herself', 'themselves', 'myself', etc.

When used with a toneless verb tense such as the perfect, the object-marker has a high tone, but in some tenses such as the present habitual, the tone is lost:[43]

- nd-a-mú-ona 'I have seen him'

- ndí-ma-mu-óna 'I usually see him'

With the imperative or subjunctive, the tone of the object-marker goes on the syllable following it, and the imperative ending changes to -e:[44]

- ndi-pátse-ni mpungá 'could you give me some rice?'

- ndi-thándízé-ni! 'help me!'

- mu-mu-thándízé 'you should help him'

Variety of tenses

lembaChichewa chili na viyowoyero vinandi, ndipo vinyake vikupambana na viyowoyero vinyake vya ku Europe. Para munthu wakuyowoya lizgu la ciyowoyero cinyake, wakuŵa na vilembo vyakwambilira nga ni -na- na -ku-, ndipo para wakuyowoya lizgu linyake wakuŵa na vilembo vyakwambilira.

Near vs. remote

lembaPali nyengo zinkhondi (zamunthazi, zamunthazi, zamunthazi, zamunthazi, na zamunthazi). Mphambano pakati pa nyengo zakufupi na zakutali njakwenelera yayi. Nyengo zakutali zikugwiliskirika nchito yayi pa vinthu ivyo vikacitika muhanya uno panji usiku wamara, kweni nyengo zakufupi zingagwiriskirika nchito pa vinthu ivyo vikacitika kumasinda panji kunthazi:

- ndi-ná-gula 'I bought (yesterday or some days ago)' (remote perfect)

- nd-a-gula 'I have bought (today)' (perfect)

- ndi-ku-gúla 'I am buying (now)' (present)

- ndí-gula 'I'll buy (today)' (near future)

- ndi-dzá-gula 'I'll buy (tomorrow or later)' (remote future)

Perfect vs. past

lembaPali mphambano yinyake pakati pa vinthu viwemi na viheni. Vinthu viŵiri ivi vikulongora kuti ivyo vikacitika vikaŵa na umaliro uwo ulipo. Nyengo ziŵiri izo zajumpha zikulongora kuti cigaŵa ico cacitika cazgoka:

Recent time (today):

- nd-a-gula 'I have bought it' (and still have it) (Perfect)

- ndi-na-gúla 'I bought it (but no longer have it)' (Recent Past)

Remote time (yesterday or earlier):

- ndi-ná-gula or ndi-dá-gula 'I bought it' (and still have it) (Remote Perfect)

- ndí-ná-a-gúla or ndí-dá-a-gúla 'I bought it (but no longer have it)' (Remote Past)

When used in narrating a series of events, however, these implications are somewhat relaxed: the Remote Perfect is used for narrating earlier events, and the Recent Past for narrating events of today.[45]

Perfective vs. imperfective

lembaAnother important distinction in Chewa is between perfective and imperfective aspect. Imperfective tenses are used for situations, events which occur regularly, or events which are temporarily in progress:

- ndi-nká-gúlá 'I used to buy', 'I was buying (a long time ago)'

- ndi-ma-gúla 'I was buying (today)', 'I used to buy (a long time ago)'

- ndí-zi-dza-gúla 'I will be buying (regularly)'

In the present tense only, there is a further distinction between habitual and progressive:

- ndí-ma-gúla 'I buy (regularly)'

- ndi-ku-gúla 'I am buying (currently)'

Other tenses

lembaOne future tense not found in European languages is the -ká- future, which 'might presuppose an unspoken conditional clause':[46]

- ndí-ká-gula 'I will buy' (if I go there, or when I get there)

There are also various subjunctive and potential mood tenses, such as:

- ndi-gulé 'I should buy'

- ndi-zí-gúlá 'I should be buying'

- ndi-dzá-gúlé 'I should buy (in future)'

- ndi-nga-gule 'I can buy'

- ndi-kadá-gula 'I would have bought'

Negative tenses

lembaNegative tenses, if they are main verbs, are made with the prefix sí-. They differ in intonation from the positive tenses.[47] The negative of the -ná- tense has the ending -e instead of -a:

- sí-ndí-gula 'I don't buy'

- sí-ndi-na-gúle 'I didn't buy'

Tenses which mean 'will not' or 'have not yet' have a single tone on the penultimate syllable:

- si-ndi-dza-gúla 'I won't buy'

- si-ndi-na-gúle 'I haven't bought (it) yet'

Infinitives, participial verbs, and the subjunctive make their negative with -sa-, which is added after the subject-prefix instead of before it. They similarly have a single tone on the penultimate syllable:

- ndi-sa-gúle 'I should not buy'[48]

- ku-sa-gúla 'not to buy'

Dependent clause tenses

lembaThe tenses used in certain kinds of dependent clauses (such as relative clauses and some types of temporal clauses) differ from those used in main clauses. Dependent verbs often have a tone on the first syllable. Sometimes this change of tone alone is sufficient to show that the verb is being used in a dependent clause.[49][21] Compare for example:

- a-ku-gúla 'he is buying'

- á-kú-gúla 'when he is buying' or 'who is buying'

Other commonly used dependent tenses are the following:

- ndí-tá-gúla 'after I bought/buy'

- ndí-sa-na-gúle 'before I bought/buy'

There is also a series of tenses using a toneless -ka- meaning 'when' of 'if', for example:[50][51]

- ndi-ka-gula 'when/if I buy'

- ndi-ka-dzá-gula 'if in future I buy'

- ndi-ka-má-gúlá 'whenever I buy'

- ndí-ka-da-gúla 'if I had bought'

Verb extensions

lembaAfter the verb stem one or more extensions may be added. The extensions modify the meaning of the verb, for example:

- gul-a 'buy'

- gul-ir-a 'buy for' or 'buy with' (applicative)

- gul-ir-an-a 'buy for one another' (applicative + reciprocal)

- gul-ik-á 'get bought', 'be for sale' (stative)

- gul-its-a 'cause to get bought, i.e. sell' (causative)

- gul-its-idw-a 'be sold (by someone)' (causative + passive)

The extensions -ul-/-ol- and its intransitive form -uk-/-ok- are called 'reversive'. They give meanings such as 'open', 'undo', 'unstick', 'uncover':

- tseg-ul-a 'open (something)'

- tseg-uk-á 'become open'

- thy-ol-a 'break something off'

- thy-ok-á 'get broken off'

- mas-ul-a 'undo, loosen'

- mas-uk-á 'become loose, relaxed'

Most extensions, apart from the reciprocal -an- 'one another', have two possible forms, e.g. -ir-/-er-, -idw-/-edw-, -its-/-ets-, -iz-/-ez-, -ul-/-ol-, -uk-/-ok-. The forms with i and u are used when the verb stem has a, i, or u. u can also follow e:

- kan-ik-á 'fail to happen'

- phik-ir-a 'cook for someone'

- gul-its-a 'sell'

- sungun-ul-a 'melt (transitive)'

- tseg-ul-a 'open'

The forms with e are used if the verb stem is monosyllabic or has an e or o in it:[52]

- dy-er-a 'eat with'

- bwer-ez-a 'repeat'

- chok-er-a 'come from'

Extensions with o are used only with a monosyllabic stem or one with o:

- thy-ok-á 'get broken off'

- ton-ol-a 'remove grains of corn from the cob'

The extension -its-, -ets- with a low tone is causative, but when it has a high tone it is intensive. The high tone is heard on the final syllable of the verb:

- yang'an-its-its-á 'look carefully'

- yes-ets-á 'try hard'

The applicative -ir-, -er- can also sometimes be intensive, in which case it has a high tone:

- pit-ir-ir-á 'carry on, keep going'

Verbs with -ik-, -ek-, -uk-, -ok- when they have a stative or intransitive meaning also usually have a high tone:

- chit-ik-á 'happen'

- sungun-uk-á 'melt (intransitive), get melted'

However, there are some low-toned exceptions such as on-ek-a 'seem' or nyam-uk-a 'set off'.[53]

Literature

lembaStory-writers and playwrights

lembaThe following have written published stories, novels, or plays in the Chewa language:

- William Chafulumira[54]

- Samuel Josia Ntara or Nthala[55]

- John Gwengwe[56]

- E.J. Chadza

- Steve Chimombo

- Whyghtone Kamthunzi

- Francis Moto

- Bonwell Kadyankena Rodgers

- Willie Zingani

- Barnaba Zingani

- Jolly Maxwell Ntaba[57]

Poets

lembaTown Nyanja (Zambia)

lemba| Town Nyanja | |

|---|---|

| Native to | Zambia |

| Region | Lusaka |

Nyanja-based | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | None (mis) |

| Glottolog | None |

none[3] | |

An urban variety of Nyanja, sometimes called Town Nyanja, is the lingua franca of the Zambian capital Lusaka and is widely spoken as a second language throughout Zambia. This is a distinctive Nyanja dialect with some features of Nsenga, although the language also incorporates large numbers of English-derived words, as well as showing influence from other Zambian languages such as Bemba. Town Nyanja has no official status, and the presence of large numbers of loanwords and colloquial expressions has given rise to the misconception that it is an unstructured mixture of languages or a form of slang.

The fact that the standard Nyanja used in schools differs dramatically from the variety actually spoken in Lusaka has been identified as a barrier to the acquisition of literacy among Zambian children.[58]

The concords in Town Nyanja differ from those in Chichewa described above. For example, classes 5 and 6 both have the concord ya- instead of la- and a-; class 8 has va- instead of za-; and 13 has twa- instead of ta-.[59] In addition, the subject and object marker for "I" is ni- rather than ndi-, and that for "they" is βa- (spelled "ba-") rather than a-.[60]

Sample phrases

lemba| English | Chewa (Malawi)[61] | Town Nyanja (Lusaka)[62] |

|---|---|---|

| How are you? | Muli bwanji? | Muli bwanji? |

| I'm fine | Ndili bwino | Nili bwino / Nili mushe |

| Thank you | Zikomo | Zikomo |

| Yes | Inde | Ee |

| No | Iyayi/Ayi | Iyayi |

| What's your name? | Dzina lanu ndani?[63] | Zina yanu ndimwe bandani? |

| My name is... | Dzina langa ndine... | Zina yanga ndine... |

| How many children do you have? | Muli ndi ana angati? | Muli na bana bangati? ('b' = [ŵ]) |

| I have two children | Ndili ndi ana awiri | Nili na bana babili |

| I want... | Ndikufuna... | Nifuna... |

| Food | Chakudya | Vakudya |

| Water | Madzi | Manzi |

| How much is it? | Ndi zingati? | Ni zingati? |

| See you tomorrow | Tionana mawa | Tizaonana mailo |

| I love you | Ndimakukonda | Nikukonda |

Ukaboni

lemba- ↑ Thambalwam, lwam. "Chewa language". Document Analysis System (in Chewa). doi:10.1177/09719458211003380. ISSN 0971-9458. S2CID 253239262.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ↑ Mikael Parkvall, "Världens 100 största språk 2007" (The World's 100 Largest Languages in 2007), in Nationalencyklopedin

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Jouni Filip Maho, 2009. New Updated Guthrie List Online

- ↑ Kishindo (2001), p.265.

- ↑ For spelling Chinyanja cf. Lehmann (1977). Both spellings are used in Zambia Daily Mail articles.

- ↑ Kamwendo (2004), p.278.

- ↑ See Language Mapping Survey for Northern Malawi (2006), pp.38–40 for a list of publications.

- ↑ "Voyager Greetings". Archived from the original on 2016-10-25. Retrieved 2016-01-02.

- ↑ Rebmann (1877) s.v. M'ombo.

- ↑ Batteen (2005).

- ↑ Downing & Mtenje (2017), p. 95: "A high vowel is very short and not very vowel-like, so inserting one leads to minimal deviation from the pronunciation of the word in the source language."

- ↑ Atkins (1950), p.200.

- ↑ Scotton & Orr (1980), p.18.

- ↑ Atkins (1950), p.207; Stevick et al. (1965), p.xii; Downing & Mtenje (2018), p. 43, quoting Price (1946).

- ↑ Kishindo (2001), p.268.

- ↑ See also Chirwa (2008).

- ↑ Atkins (1950), p.209.

- ↑ Watkins (1937), p.13.

- ↑ Mchombo (2004), p.10.

- ↑ Mtanthauziramawu wa Chinyanja (2002).

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Stevick et al. (1965), p.147.

- ↑ Mchombo (2004), pp.17–18.

- ↑ Hullquist (1988), p.145.

- ↑ Downing & Mtenje (2017), p. 263.

- ↑ Mtanthauziramawu wa Chinyanja.

- ↑ Corbett & Mtenje (1987), p. 10.

- ↑ Scott & Hetherwick (1929), s.v. Ibsi; Rebmann (1877) s.v. Chiko, Psiwili/Pfiwili; Watkins (1937), p. 37.

- ↑ Rebmann (1877) s.v. Aya, Mame, Mano, Yonse; cf Goodson (2011).

- ↑ Rebmann (1877), s.v. Ufa; Watkins (1937), pp. 33–4.

- ↑ Maxson (2011), pp.39ff, 77ff.

- ↑ For tones, Mtenje (1986).

- ↑ Maxson (2011), p.126.

- ↑ Maxson (2011), p.115.

- ↑ Salaun, p.49.

- ↑ Kiso (2012), p.107.

- ↑ Hyman & Mtenje (1999a).

- ↑ Maxson (2011), p.52.

- ↑ Maxson (2011), p.36.

- ↑ Salaun, p.16.

- ↑ Maxson (2011), pp. 21, 23.

- ↑ Maxson (2011), pp.26ff.

- ↑ Maxson (2011), p.64.

- ↑ Downing & Mtenje (2017), pp. 143, 162.

- ↑ Downing & Mtenje (2017), pp. 142, 145.

- ↑ Kiso (2012), pp. 110–111.

- ↑ Maxson (2011), p. 116.

- ↑ Mtenje (1986), p. 244ff.

- ↑ Stevick et al. (1965), p.222.

- ↑ Mchombo (2004), pp. 17–18.

- ↑ Salaun, p.70

- ↑ Kanerva (1990), p.24.

- ↑ Salaun, p.78.

- ↑ Hyman & Mtenje (1999b).

- ↑ "Chafulumira, William". Dictionary of African Christian Biography.

- ↑ WorldCat list of Ntara's publications

- ↑ "Whither Vernacular Fiction?". The Nation newspaper May 26, 2017.

- ↑ "Jolly Maxwell Ntaba". The Nation newspaper April 4, 2014

- ↑ Williams, E (1998). Investigating bilingual literacy: Evidence from Malawi and Zambia (Education Research Paper No. 24). Department for International Development.

- ↑ Gray, Lubasi, & Bwalya (2013), p. 11

- ↑ Gray, Lubasi & Bwalya (2013) p. 16.

- ↑ Paas (2016).

- ↑ Phrases from Gray et al. (2013).

- ↑ Maxson (2011), p. 112.

Mabuku

lemba- Atkins, Guy (1950) "Suggestions for an Amended Spelling and Word Division of Nyanja" Africa: Journal of the International African Institute, Vol. 20, No. 3

- Batteen, C. (2005). "Syntactic Constraints in Chichewa/English code-switching." Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- Bickmore, Lee (2021). "Town Nyanja Verbal Tonology".

- Chirwa, Marion N. (2008). Trill Maintenance and Replacement in Chichewa (M.A. thesis, University of Cape Town)

- Corbett, G.G.; Al D. Mtenje (1987) "Gender Agreement in Chichewa". Studies in African Linguistics Vol 18, No. 1.

- Downing, Laura J.; Al D. Mtenje (2017). The Phonology of Chichewa. Oxford University Press.

- Goodson, Andrew, (2011). Salimini's Chichewa In Paas, Steven (2011). Johannes Rebmann: A Servant of God in Africa before the Rise of Western Colonialism, pp. 239–50.

- Gray, Andrew; Lubasi, Brighton; Bwalya, Phallen (2013). Town Nyanja: a learner's guide to Zambia's emerging national language.

- Hetherwick, Alexander (1907). A Practical Manual of the Nyanja Language ... Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- Henry, George, (1904). A grammar of Chinyanja, a language spoken in British Central Africa, on and near the shores of Lake Nyasa.

- Hullquist, C.G. (1988). Simply Chichewa.

- Hyman, Larry M. & Sam Mchombo (1992). "Morphotactic Constraints in the Chichewa Verb Stem". Proceedings of the Eighteenth Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society: General Session and Parasession on The Place of Morphology in a Grammar (1992), pp. 350–364.

- Hyman, Larry M. & Al D. Mtenje (1999a). "Prosodic Morphology and tone: the case of Chichewa" in René Kager, Harry van der Hulst and Wim Zonneveld (eds.) The Prosody-Morphology Interface. Cambridge University Press, 90–133.

- Hyman, Larry M. & Al D. Mtenje (1999b). "Non-Etymological High Tones in the Chichewa Verb", Malilime: The Malawian Journal of Linguistics no.1.

- Katsonga-Woodward, Heather (2012). Chichewa 101. ISBN 978-1480112056.

- Kanerva, Jonni M. (1990). Focus and Phrasing in Chichewa Phonology. New York, Garland.

- Kishindo, Pascal, (2001). "Authority in Language": The Role of the Chichewa Board (1972–1995) in Prescription and Standardization of Chichewa. Journal of Asian and African Studies, No. 62.

- Kiso, Andrea (2012). "Tense and Aspect in Chichewa, Citumbuka, and Cisena". Ph.D. Thesis. Stockholm University.

- Kunkeyani, Thokozani (2007). "Semantic Classification and Chichewa Derived Nouns". SOAS Working Papers in Linguistics Vol.15 (2007): 151–157.

- Laws, Robert (1894). An English–Nyanja dictionary of the Nyanja language spoken in British Central Africa. J. Thin. pp. 1–. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- Lehmann, Dorothea (1977) An outline of Cinyanja Grammar. Zambia ISBN 9789982240154

- Mapanje, John Alfred Clement (1983). "On the Interpretation of Aspect and Tense in Chiyao, Chichewa, and English". University College London PhD Thesis.

- Marwick, M.G., (1963). "History and Tradition in East Central Africa Through the Eyes of the Northern Rhodesian Cheŵa", Journal of African History, 4, 3, pp. 375–390.

- Marwick, M.G., (1964). "An Ethnographic Classic Brought to Light" Africa: Journal of the International African Institute, Vol. 34, No. 1, pp. 46–56.

- Maxson, Nathaniel (2011). Chicheŵa for English Speakers: A New and Simplifed Approach. ISBN 978-99908-979-0-6.

- Mchombo, Sam A. (2004), The Syntax of Chichewa, Cambridge Syntax Guides, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. XV + 149, ISBN 0-521-57378-5, retrieved June 11, 2019

- Mchombo, S. (2006). "Nyanja". In The Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World (Elsevier).

- Missionários da Companhia de Jesus, (1963). Dicionário Cinyanja–Português. Junta de Investigaçôes do Ultramar.

- Mtanthauziramawu wa Chinyanja/Chichewa: The first Chinyanja/Chichewa monolingual dictionary (c.2000). Blantyre (Malawi): Dzuka Pub. Co. (Also published online at the website of the "Centre for Language Studies of the University of Malawi".)

- Mtenje, Al D. (1986). Issues in the Non-Linear Phonology of Chichewa part 1. Issues in the Non-Linear Phonology of Chichewa part 2. PhD Thesis, University College, London.

- Mtenje, Al D. (1987). "Tone Shift Principles in the Chichewa Verb: A Case for a Tone Lexicon", Lingua 72, 169–207.

- Newitt, M.D.D. (1982) "The Early History of the Maravi". The Journal of African History, vol 23, no. 2, pp. 145–162.

- Paas, Steven, (2016). Oxford Chichewa–English, English–Chichewa Dictionary. Oxford University Press.

- Rebman, John (= Johannes Rebmann), (1877). A Dictionary of the Kiniassa Language. Church Missionary Society (reprinted Gregg, 1968).

- Riddel, Alexander (1880). A Grammar of the Chinyanja Language as Spoken at Lake Nyassa: With Chinyanja–English and English–Chinyanja Vocabularies. J. Maclaren & Son. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- Salaun, N. (1993) [1978]. Chicheŵa Intensive Course. Likuni Press, Lilongwe.

- Scott, David Clement & Alexander Hetherwick (1929). Dictionary of the Nyanja Language.

- Scotton, Carol Myers & Gregory John Orr, (1980). Learning Chichewa, Bk 1. Learning Chichewa, Bk 2. Peace Corps Language Handbook Series. Peace Corps, Washington, D.C. (For recordings, see External links below.)

- Simango, Silvester Ron (2000). "'My Madam is Fine': The Adaptation of English loanwords in Chichewa". Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, vol 12, no. 6.

- Stevick, Earl et al. (1965). Chinyanja Basic Course. Foreign Service Institute, Washington, D.C. (Recordings of this are available on the internet.)

- Wade-Lewis, Margaret (2005). "Mark Hanna Watkins". Histories of Anthropology Annual, vol 1, pp. 181–218.

- Watkins, Mark Hanna (1937). A Grammar of Chichewa: A Bantu Language of British Central Africa, Language, Vol. 13, No. 2, Language Dissertation No. 24 (Apr.-Jun., 1937), pp. 5–158.

- Woodward, M.E., (1895). A vocabulary of English–Chinyanja and Chinyanja–English as spoken at Likoma, Lake Nyasa. Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge.

Vigaŵa vya kuwalo

lemba- Omotola Akindipe, George Kondowe, Learn Chichewa on Mofeko

- Online English–Chichewa Dictionary

- My First Chewa Dictionary kasahorow

- Chichewa at Omniglot

- English / Chichewa (Nyanja) Online Dictionary

- Buku Lopatulika Bible, 1922 version digitalized

- Complete Bible (Buku Lopatulika, 1922, revised 1936) in Nyanja, chapter by chapter

- Buku Lopatulika Bible, 2014 version

- Johnson's 1912 translation of Genesis 1–3 into the Likoma dialect, in various formats

- Johnson's translation of the Book of Common Prayer in the Likoma dialect (1909).

- Holy Quran in Chichewa

- Recordings of pages of Scotton & Orr's Learning Chichewa Archived 2017-10-11 at the Wayback Machine

- Willie T. Zingani, Idzani muone "Come and see" Chichewa book in pdf form.

- Bonwell Kadyankena Rodgers, [1]. Agoloso Presents – Nkhokwe ya Zining'a za m'Chichewa.pdf.

- Bonwell Kadyankena Rodgers, [2]. Agoloso Presents – Mikuluwiko ya Patsokwe.pdf.

- OLAC resources in and about the Nyanja language

- Zodiak Radio live radio in English and Chichewa

- M.V.B. Mangoche A Visitor's Notebook of Chichewa Elementary phrasebook.

- Complete recording of Buku Loyera New Testament (without text)